In the month of September 1700, the Swedish troops garrisoning the town of Narva, a small but strategically significant settlement near the East Baltic coastline, found themselves under a state of siege. The besiegers were the soldiers of Tsar Peter the Great. The Russian monarch had decided that at last the time was ripe to capture his "window on, the West" - meant to create a Russian presence in the Baltic.

To this end, he entered into a triple alliance with Denmark and Saxony, two other states with much to gain at Sweden's expense. All three powers were confident in their actions, as the Swedish army was tiny compared to their collective strength, and the Swedish monarch, Charles XII, was a teenager, and inexperienced in war and statecraft. Here was stealing candy from a baby on a very grand scale indeed.

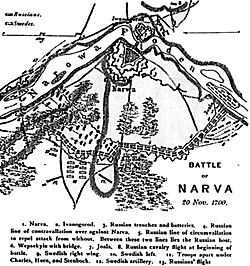

The Swedes garrisoning Narva were as aware of this as the Tsar, but still "they grimly defended their positions. In front of them they could see the Russian forces daily building up, and the siege works grew more extensive and more complete. Narva itself lay in a bend of the river Narova, on a bridging point, which connected it with the old citadel of Ivanogrod., Ile Russian siegeworks took the form of a vast arc, bending away from the town, with its ends resting on the banks of the river.

After the initial circumvallation had been built to keep the defenders in, the Russians turned to defending their own lines. To guard the main road into Narva a raised platform was constructed, fortified and provided with artillery. This bastion was duly dubbed "Fort Troubetsky" in honour of its commanding officer.

To guard against any attempts to raise the siege from the east, a line of contravallation was raised, reinforced by deep trenches, parapets, che;wyx de hive and palisades. To the south of Fort Troubetsky the two lines of fortifications ran more or less parallel to each other, with a' distance of between 30 to 50 metres between them. To the north of Fort Troubetsky, the lines were inclined a little to the west, partly to take advantage of the lie of the land, and partly to protect a pontoon bridge which had been thrown across the river near by the viiiage of Kamperholm. As the permanent bridge across the river Narova was controlled by the garrison of Narva, the pontoon bridge was the sole line of communication between the Russian army and their home country. By the time of the climax of the siege, the besieging force numbered over 70,000 men and 180 guns.

By October, a strange rumour began to sweep through the Russian lines. Incredible as it seemed, the Swedes, instead of suing for peace, had actually taken up the gauntlet and in a bold counterstroke had invaded Denmark and forced the Danes out of the war. Perhaps a little more disquieting was the rumour that an Army of the same madmen led by their boy-king was sailing across the Baltic to raise the siege of Narva.

Huddled behind the ramparts of their massive siegeworks, the Russians became more uneasy, as on November 18th and 19th, a steady stream of beaten and frightened troops began to straggle into camp bearing tales of how an unstoppable force was pushing in all of the outposts and pickets, and was less than a day's march away. These may have only been rumours, but they certainly had a dramatic effect on one participant in the siege.

Peter I Romanov, Tsar of all the Russians, was at Narva to oversee the final stages of his triumph. However, upon hearing about the nearby presence of the Swedes, he decided precipitately that he was needed elsewhere. "Elsewhere", was anywhere in fact where the Swedes were not about to arrive, and under pretext of visiting a more southerly force of soldiers sent to head off the Swedes, left the camp so quickly, he abandoned his jewels and his personal case of champagne. Behind him he left a Frenchman, the Duc du Croy, to oversee the Russian forces. This worthy had only been present at the siege as a neutral observer. He spoke no Russian, had little regard for the qualities of the Russian peasant soldier, and was unwilling to undertake the job. Peter himself had to "persuade" the nobleman to undertake the task, and when Peter the Great under the influence of several bottles of brandy personally persuaded you to do something it was a very strong man, indeed who was not persuaded!

So, 70,000 Russians, admittedly ill-equipped and trained, stood behind their defences and cannon and waited. What professional officers they had spoke German or French only, and were mistrusted, while those native Russian officers were noted for drunkenness or stupidity, or both. But numbers and position were solidly on their side.

What of the Swedes?

But what of the Swedes? Charles XII had led his me ' n in a punishing march to reach Narva, with little rest, no food and in the teeth of the Winter Baltic elements. The sheer haste of his breakneck march had had its toll, and the Swedish force that reached Narva on 20th November numbered no more than 10,500 men. Even with the best troops in Europe, what could Charles and his generals hope to do to the massive Russian defences?

The answer was reached fairly quickly. Sitting on the hill overlooking the Russian positions, the Swedes saw the two major weaknesses in the Russian position. Firstly, the sheer number of men packed into the constricted space of the two defensive lines meant that Russian lateral communication and maneuvre was almost impossible. Secondly, the Russians had only one escape route to home soil - the pontoon bridge.

Contemporary military practice, as conducted by gentlemen in more southerly climes would have meant that the Swedes should have begun a lengthy siege, digging saps and approaches. However, sieges of this type were conducted when the attackers outnumbered the defenders, and not vice versa. Moreover, as readers of my earlier pieces on the Swedish army of this period may remember, the Swedish monarch's temperament was not fitted for patient spadework. The only option was immediate attack, and plant were drawn up accordingly.

Points of Attack

Battle of Narva 1700 Large Map (slow: 116K)

Battle of Narva 1700 Large Map (slow: 116K)

Two principal points of attack were decided upon, one either side of Fort Troubetsky. The Foot were split into two groups, and formed into deep columns of attack, the right hand force under General Otto Vellingk, the left under General Carl Gustav Rhenskiold. The artillery under master gunner Johan Sjobladh was also divided into two groups, one to engage in countcr battery fire with the Sun& of Fort Troubetsky, the other to support the attack of the infantry columns. To facilitate this dual role, the artillery was formed into one large body, and placed in between the two groups of Foot. This use of massed infantry columns and artillery support would seem to belong more to the age of Napoleon than of Marlborough, but as in everything else, the Swedes preferred to be the exception rather than the rule.

The Horse reserve under Johann Ribbing was placed to the rear of the left hand infantry column. Their task was to exploit the initial breakthrough and by riding through the breaches established by the foot sweep to the rear of the Russian positions and cut off the lines of retreat.

The two main bodies of Horse were placed on the extreme flanks of the infantry columns. Their initial task was to demonstrate along the length of then fortifications, attracting the attention of the defenders, and at the same time preventing them from making a flank. attack on the columns by sallying over the defence works. This turned out to be an unnccessary precaution, as the Russians remained resolutely attached to their fortifications.

Charles had thus deployed his army so as to concentrate his numerically inferior forces at two narrow points. The Russians, deployed on a long and constrictive front were to be unable to concentrate their vastly superior forces to counter their enemy. In effect, the sheer size of the ill-trained army was to be used against it.

Attack

At 2 o'clock in the afternoon, the attack commienced. With the grenadiers formed as the front of the attacking columns, the Foot began their assault. Equipped with fascines, they were to storm the Russian positions in the fashion they had learnt so well - a point blank volley and a charge to finish the job with cold steel.

As the attack was launched, it seemed that the Swedes had recruited the weather on to their side. A sudden and heavy snow began, with the wind blowing directly into the faces of the defenders. The Russian artillery tried to, bear on the advancing columns, but inflicted few casualties. The blank white wall of snow conspired to hide the heads of the advancing columns until they were within 30 metres of the entrenchments. At this stage, both bombardiers and musketeers attempted to stop the bluecoats, but in their agitated states fired high or wide. Looming out of the snowfall, the Swedes checked slightly to deliver a single devastating volley, and with shouts of "Fall On!" and "God our Help", charged forward to the extreme discomfort of those brave or foolish souls who still held their posts.

The breaches in the Russian lines were made within fifteen minutes of the start of the attack, and in less than half an hour, the Russian lines had been so badly ruptured that all transmission of orders became impossible. The Russian higher command, always suspect, was now totally non-existent!

However, that was not to say that the Swedes had won the battle. Far from i4 for on a man to man basis they were still heavily outnumbered. Prompt and decisive action was required to keep the advantage. Accordingly, Vellingk led his columns of troopers through the breaches, and then obliquely to the right, thus outflanking the main body of the Russian left wing. Rhenskiold on the left executed a similar movement, channeling the movement of the Russians back to their sole line of retreat, the pontoon bridge.

In the south, it was General Wiede's Russians who took the brunt of the attack, being forced away from their original positions, eventually to adopt a defensive position on an area of high ground behind the lines. The Russian Horse who were positioned to his rear took one look at the advancing Swedes, and decided that they would best serve Mother Russia by saving themselves to fight another day. In their panic, many attempted to swim the Narova. Unfortunately for them, the river proved to be swift and dangerous. One estimate places the loss of life by drowning in this single incident at over one thousand men and horses.

To the north, the Swedish advance went as planned, and the panic-stricken Russians were herded through their camp and towards the bridge. With all military organisation fast disappearing, the pontoon bridge was soon choked by a thronging mass of Russian peasantry. The inevitable happened, and the bridge collapsed, drowning many, but also cutting off the only practical escape route for some 70,000 Russians.

Battle of Narva 1700 Large Illustration (slow: 119K)

Battle of Narva 1700 Large Illustration (slow: 119K)

Battle of Narva 1700 Jumbo Illustration (very slow: 248K)

As often happens in these situations, individuals and units found some resolve, and a hasty defence was now conducted. The Semoienevski and Precoaebasjhenski regiments - the Tsar's Guards, and the best troops in the army, built a makeshift fort out of overturned wagons, and began the most tenacious defense of them battle. In fact, in terms of Swedish casualties, and length of resistance, this and general Wiede's stubborn resistance in the south mark-the real battle of Narva.

So great did the Guards' resistance become that Charles was obliged to send for Vellingk's command to reinforce his attacks on the barricade. A holding force was left to ensure that Wiede's command did not get up to any mischief. Fort Troubetsky had to be stormed, and it was the eventual fall of this strongpoint that saw the resistance finally begin to die down. Even so, it was not until 8 o'clock in the evening that the surrender of the Guards was obtained, and Wiede held out until two hours after midnight. With the fall of this last force, the Swedish triumph was complete.

When one considers the odds involved in the battle, the casualty figures for both sides are also truly impressive. Total Rusian dead and wounded may have been as high as 20,000, all of the remainder being taken prisoner. All of the Russian baggage train, supplies, artillery and wagons fell to the conquerors, as well as vast amounts of colours. Against this, the Swedes lost about 700 killed and 1200 wounded.

Dramatic Victory

A dramatic victory indeed. The results were many and varied. Certainly it made the rest of Europe sit up and take notice of the boy-king of Sweden. From this point onwards until his death he was treated as a potential ally and a feared enemy by the rest of Europe. By 1707, both France and the Maritime Powers were attempting to sway him into aligning himself with them. The intervention of the Swedish army at that stage of the War of the Spanish Succession would have been dramatic to say the least, and is surely the basis of a fascinating "what it" campaign.

To the Russians, Narva was a crushing blow. Yet, it proved to be a temporary one. Peter rebuilt his army, and even learnt from his mistakes and failures. Better officers were recruited, soldiers were trained and equipped more thoroughly. It was to be a long time before the Russians were to best the Swedes in battle, but the lessons taught at Narva were used to bring about Charles XII's eventual defeat on the field of battle. But that is another story.

To the Swedes, Narva marked the beginning of a whole series of military successes and triumphs, where to bring an enemy to battle was to, beat him, no matter what the odds. Unfortunately, the very case of this extraordinary victory proved to be self-defeating, in that it seemed to give Charles a feeling of contempt for the Russian army that he was unable to shake off, and instead of taking the opportunity to finish off his most implacable opponent caused him to waste the next years thrashing his enemies in Saxony and Poland, thus giving Peter his much-needed breathing space to recruit and-develop his forces.

Part 2: Battle of Narva: 20th November 1700

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com