With the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, Union forces took a giant step toward accomplishing their grand strategy -- to split the Southern Confederacy from north to south along the Mississippi valley. Earthen forts, rifle pits, and water batteries mounting heavy ordnance attested to the Confederate desire to guard natural invasion routes into the hinterland.

With the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, Union forces took a giant step toward accomplishing their grand strategy -- to split the Southern Confederacy from north to south along the Mississippi valley. Earthen forts, rifle pits, and water batteries mounting heavy ordnance attested to the Confederate desire to guard natural invasion routes into the hinterland.

But on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers was forged a vital cog in final Union victory -- joint operations between land and naval forces capable of overcoming position defense and indecisive leadership. From the campaign emerged a new Union general -- Ulysses S. Grant -- and the beginning of the end of the war was heralded as early as 1862 with the Confederate loss of these two forts.

The rivers of the antebellum South were important for commercial development as steamboats not only carried cotton, tobacco, iron, and grain to market, but also provided a chain of communication between cities such as Louisville, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Nashville and interior hamlets and plantations. Such a vital peacetime factor as the rivers would naturally have value in war. Good roads were few and railroads were in their natal state.

Lacking a navy, the young Confederacy turned to static defense of its waterways and in mid-1861, Tennessee state authorities constructed fortifications to guard the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. After violation of Kentucky neutrality by Confederate authorities in September, Forts Henry and Heiman on the former stream and Fort Donelson on the latter were strengthened and became a vital link -- albeit a weak one -- in the defense line which stretched from the Alleghenies to the Mississippi.

Thin Line of Grey

Indeed, it was a thin line of gray since the Confederacy could muster little more than 40,000 under-equipped and ill-trained volunteers to garrison such strong points as Columbus, Kentucky, the "Twin Rivers forts," Bowling Green, and Cumberland Gap. General Albert Sidney Johnston was the theater commander for the Confederacy; a man considered by some to be the foremost American soldier of the era. But his assignment was immense. Confederate Department Number 2 included Kentucky, Missouri, and the Indian Territory. The central government in Richmond o n l y dimly perceived Johnston's materiel and manpower needs, and states rightism impeded efforts to draw upon the resources of individual state governments in order to provide for the total defense of the western Confederacy.

Johnston, for example, could secure only 1,000 of an estimated 30,000 muskets needed by his forces and he consequently impressed civilian hunting pieces and shotguns. Furthermore, the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers all bisected Johnston's zone of defense and all came together in Northern-held territory. The Ohio shielded the states of the Northwest from the threat of Southern invasion and utilization of that river permitted Federal authorities to transfer units and equipment rapidly from one wing of the Union forces to the other.

Overwhelming Union superiority in gunboats and transports on western waters converted these natural features into a formidable military advantage. Thus, Johnston could only dig in and hold with his skeleton forces long enough for Confederate authorities to reinforce him adequately and to enable Southern leaders in Kentucky to woo citizens to their cause.

Union Problems

If Confederate authorities suffered from green troops, logistical and strategic nightmares, and intractable politicians, their Federal counterparts also had problems. Union command in the west was divided between the Department of the Missouri at St. Louis and the Department of the Ohio at Louisville. John C. Fremont, and subsequently Henry Halleck, commanded upwards of 70- to 80,000 in the former department while a succession of commanders culminating with Don Carlos Buell had charge of the approximately 40-45,000 man Ohio department. The boundary between the two was the Cumberland river. Seemingly baffled by munitions shortages, red tape, and consistent overestimates of Johnston's strength, seizure of the initiative devolved upon two subordinates, one an army man, the other from the navy.

Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, a little-known local commander at Cairo, Illinois, and crusty, salt-water sailor, Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote were both anxious to close with the enemy and breach the Confederate defense line. Despite later controversies as to who proposed the Twin Rivers campaign, both Foote and Grant badgered the hesitant Halleck for permission to smash Fort Henry by land and water. Halleck, overly cautious, due mainly to some superb deception by Johnston, procrastinated until rumors of Confederate reinforcements from the east -- fifteen regiments and the redoubtable General P.G.T. Beauregard, the hero of Manassas -- and a minor Union victory at Mill Springs in Buell's department -- spurred him to action.

On January 30, he hesitatingly approved the Grant/Foote expedition.

Operations in Tenn.: Feb-Mar 1862 (slow: 111K)

February 3

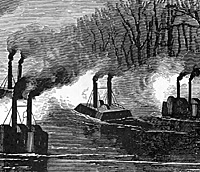

On February 3, nine transports convoying 15,000 troops and escorted by four ironclads and three timberclad gunboats steamed up the rain-swollen Tennessee toward a forward base just out of range of Fort Henry's guns. The Federal land force comprised two divisions, one commanded by a politician-turned-general, Brigadier General John A. McClemand, and the second under Brigadier General Charles F. Smith, a staunch regular who had been Grant's cadet commander at West Point.

Opposing the invasion force were some 2,800 half sick, poorly armed Confederates under a sometime civil engineer, Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, the local commander on the Twin Rivers at the time. Low lying Fort Henry was under two feet of water, torpedoes in the river were ineffective, the powder was of inferior quality, and only eleven of the seventeen guns in the fort faced the Tennessee. Fort Heiman, an incomplete earthwork across the river, had been abandoned by Tilghman in order to concentrate his meager forces at Henry where roads linked the post with Fort Donelson, twelve miles away.

Grant's plan of attack combined a pincer movement by Smith against Fort Heiman and McClernand against Fort Henry with the direct naval attack on the latter fort. But Tilghman realized the impossibility of his position and on February 6, as the joint Union force moved against him, he dispatched the majority of his garrison across country to Fort Donelson.

The Confederate brigadier remained behind with seventy artillerymen to serve the heavy ordnance against the gunboats. The battle opened about 12:30 p.m. as Foote's flotilla advanced in two divisions. The four ironclads, Essex, Cincinnati, Carondelet, and St. Louis took the lead, followed by the timberclads, Tyler, Conestoga, and Lexington, firing over the ironclads. The fleet mounted fifty-four guns but only the eighteen bow guns could be brought to bear on Fort Henry. Still, they swept the Confederate gun positions, dismounted many cannon, and spread terror.

The inexperienced Confederate gunners planted a shot in the boiler of the Essex knocking her out of action and the Cincinnati was hit thirty-two times; two of her guns were disabled, her smokestacks, main cabin, and small boats were badly damaged. Point-blank naval gunfire led Tilghman to request terms from Foote only to be rebuffed coldly: "No sir, your surrender will be unconditional!" Meanwhile, Grant's soldiers were sloshing through muddy backwaters and victory at Fort Henry belonged clearly to the U.S. Navy.

Grant realized that only half the battle had been won although his original orders mentioned nothing about capturing Fort Donelson. Seizing the initiative, he telegraphed Halleck that he planned to take and destroy Fort Donelson on February 8 and then regroup at Henry for the anticipated counter stroke by Johnston. Meanwhile, Foote exploited the strategic results of the victory as the three wooden gunboats swept all the way up the Tennessee to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. They destroyed the Memphis and Ohio railroad bridge above Fort Henry, captured iron plate and timber for shipbuilding, and spread terror among the local populace.

The 1,000-ton Essex, designed for river and coastal operations. This new ironclad under Commodore W.D. Porter mounted six guns: three 9-inch; one 10-inch; one 32-pounder; and one 12-pounder. The Essex led in the capture of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, and later took part in

the occupation of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

The 1,000-ton Essex, designed for river and coastal operations. This new ironclad under Commodore W.D. Porter mounted six guns: three 9-inch; one 10-inch; one 32-pounder; and one 12-pounder. The Essex led in the capture of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, and later took part in

the occupation of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Neither Grant nor Johnston realized how precarious was the Federal position -- isolated and dependent on a single tenuous line of communication for supplies and reinforcements. Halleck realized the situation but Johnston appeared mesmerized by Buell's potential threat. Finally, on February 7, Johnston, Beauregard, and their chief subordinates decided that the loss of Fort Henry necessitated the retirement of the western army to undetermined positions south of the Tennessee river. Polk's wing of the army and the Bowling Green force were to operate independently of one another temporarily; Nashville might have to be abandoned; the Mississippi was to be defended by a series of fortifications at Columbus, Island Number 10, Fort Pillow, and Memphis, and by Confederate gunboats. Under the repeated enjoinders of the Confederate's provisional governor of Kentucky, Johnston decided not to totally abandon the Tennessee/Cumberland forts.

Error

Instead, in a fateful and grievous error, Johnston further split his forces by sending Brigadier General Gideon Pillow from Clarksville, Tennessee, and Brigadier Generals John B. Floyd and Simon B. Buckner from Russellville, Kentucky with their troops to contain Grant at Donelson until the main Bowling Green army had cleared Nashville. Unfortunately, the instructions from the theater commander remained unclear; Johnston chose not to go in person to Donelson; and the three subordinates he sent were simply inadequate to the task at hand.

First to arrive at Donelson was Pillow, veteran of the Mexican War, lawyer and hack politician from Tennessee whose ego far surpassed his military skill.

John B. Floyd, a Virginian and former Secretary of War prior to the war, was no better although, when he assumed command at Donelson on February 13, he brought with him a veteran brigade of Virginians comprising infantry and artillery.

Perhaps the most respected of the general officers sent to Dover was Simon B. Buckner of Kentucky, but he was only third in succession of command. Still a fourth brigadier, Bushrod Johnson, was in charge of the outer defense works at the fort, but for the duration of the action he remained a cipher and only added to the confusing command setup. Still, it wasn't until February 12 that Grant could move overland against the mismatched Confederate brigadiers. Leaving Brigadier General Lew Wallace and 2,500 men behind to cover Fort Henry, Grant's force basked in the springlike weather and the roadsides were soon littered with blankets and overcoats. Foote's gunboats made the more circuitous route by water in time to join Grant on the evening of the twelfth.

Union cavalry brushed with Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest's troopers a mile west of the Confederate defenses during the overland march, and the Carondelet fired several shells at the water batteries announcing the navy's arrival. But, just as Grant anticipated, Pillow made no attempt to contest Grant's movement and merely concentrated on strengthening the static defenses.

Fort Donelson was a simple earthwork, situated atop a hill, one hundred feet above the Cumberland. Two river batteries with twelve heavy seacoast cannon commanded the stream. But the fort was especially vulnerable from the land side where deep gullies, ravines, wooded ridges, and creeks marked the countryside around Dover. To remedy this weakness, Pillow and his engineers rushed completion of a system of rifle pits fronted by abatis along the crest of high ground to the west and rear of the main fort. Fort Donelson thus became a fortified camp into which thousands of Confederates marched in early February.

More ACW Campaign for Forts Henry and Donelson

-

Forts Henry and Donelson: Introduction

Forts Henry and Donelson: Feb. 13 1862 Union Attack

Forts Henry and Donelson: Feb. 15 Confederate Counterattack

Forts Henry and Donelson: Order of Battle

Forts Henry and Donelson: Three Large Maps of Attacks (very slow: 439K)

Forts Henry and Donelson: Three Jumbo Maps of Attacks (extremely slow: 824K)

Back to Conflict Number 7 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1974 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com