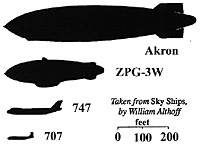

Lighter-than-air craft combine the romance of flight and the sea, and no matter how many times I see a photo of an airship, I am still amazed that something that big actually floats. As the comparative size diagram shows, airships dwarfed even a modern-day jumbo jet. Compared to the tiny wood-and-fabric planes of the era, their size was almost mythic.

Lighter-than-air craft combine the romance of flight and the sea, and no matter how many times I see a photo of an airship, I am still amazed that something that big actually floats. As the comparative size diagram shows, airships dwarfed even a modern-day jumbo jet. Compared to the tiny wood-and-fabric planes of the era, their size was almost mythic.

As the first aircraft, lighter-than-air (LTA) vehicles had a respectability that has faded; now their use is limited to advertising. In their time they were just as important as fixed wing aircraft, like helicopters are today.

History

When fixed-wing aircraft were barely able to carry one person aloft for a short time, airships were able to carry several and stay aloft for days. At the beginning of WW I, they were a reliable heavy-lift, long-endurance platform with a speed only marginally less than the fixed-wing fighters of the day. Additionally, they did not need a runway. Airships were true VTOL aircraft. The disadvantages of LTA craft were their great size and cost, their limited maneuverability, and the risks associated with their hydrogen gas. These were not show-stoppers, and like any other platform, their strengths and weaknesses suited them for some missions, but not others.

The Blimp

There are two types of military Lighter-Than-Air craft, or airships. The nonrigid airship acquired the name "blimp" during WW I. It is a streamlined gasbag with control surfaces at the rear and a gondola, or control car, suspended below it. At first, this was often a two-seater aircraft fuselage, complete with engine. A second engine might be grafted onto the rear of the fuselage to get a push-pull effect. Later gondolas were purpose-designed, but were still basically containers for the crew, engines, fuel, and the military payload of the craft.

The British used nonrigids extensively in WW I, over 300 patrolling and escorting convoys. The USA used about 140 K- and M-series blimps in WW II in the same role. In both wars, blimps were highly effective in protecting convoys against submarine attack.

There is a practical limit to the size of a blimp, about 360 feet, because the gasbag will flex, or do other strange things as its size increases. This limits its payload and endurance.

The Dirigible

The rigid airship, or dirigible, can be made much larger. These ships were built by France, Germany, Italy and Britain in WW I, with the US joining in after the wars. It has an outer envelope, braced to hold an aerodynamic shape. Inside are 4-19 gas cells.

The gondola below is larger and more sophisticated, having more space for a larger crew, more engines, and so on, as well as a usefull payload.

Rigids are much more expensive than nonrigids. A nation can build three blimps for each rigid. They also require more extensive ground handling facilities since more people (or power equipment) is needed to move them in and out of the hangar, and the hangar itself must be must much larger.

Airships have to be hangared, because they are extremely vulnerable to high winds, and their fabric envelopes have to be protected from the elements.

During the Great War

During the Great War, the Germans were the masters of rigid airship design. Count Von Zeppelin had built his first rigid, L1, in 1899. Germany quickly adopted the Zeppelin for military use, and they had the largest, most sophisticated designs throughout the Great War. Information on Zeppelin technology, obtained from wrecked ships or espionage, was a prioriy target of Allied intelligence. For example, the wrecked gondola of L49 was used as a pattern for America's first rigid, Shenandoah. German duraluminum's composition was another secret, which was not revealed until after the war. The Germans did little with nonrigid airship designs.

The Germans used their Zeppelins for maritime reconnaissance, scouting for the High Seas Fleet. They also, for many reasons, instituted the strategic bombing of England, which had a strong psychological effect on the British populace, but did little real damage. There was universal terror, and a sense of helplessness at being unable to block these attacks. The sight of a Zeppelin, hovering motionless over a ciy, dropping bombs one at a time, was a frightening vision of new technology gone wrong.

The British military could not effectively counter high-altitude attacks at night during the early part of the war, but otherwise suffered no adverse military effects. Later in the war, as antiaircraft and fighter protection improved, and especially after the introduction of incendiary machinegun ammunition in September 1916, many Zeppelins were lost. Operational losses were also high, since the long, high altitude flights strained the primitive engines and crews well beyond normal limits.

Convoy Escorts and Sub Attacks

During WW I, British nonrigids did yeoman service as convoy escorts and patrol aircraft. Like maritime patrol aircraft in WW II and today, they had the endurance to go out long distances and remain on station.

As convoy escorts, they would "sail" with the ships, stationing themselves to windward (see the movement rules) and then moving at high speed (compared to a ship and especially compared to a submerged sub) toward any sighting of a periscope or other sign of a submarine. Its height of eye allowed it to see better than the ships it protected, and its superior speed often allowed it to get to a Uboat before it could make its attack. Sometimes, in clear warer on a sunny day, it could actually see the U-boat at shallow depths, whether the scope was extended or not.

Once it was on top of the sub, early blimps would drop smoke floats, or use "wireless" to coach escorting destroyers on top of rhe sub. Even if they did not sink the sub, they achieved their mission by forcing the sub to break off its attack. Later, blimps with better payloads would make the first attack themselves, and then coach the escorts in for a follow-up.

The British started building rigids late in the Great War, and only a few were employed operationally. They were used for distant patrolling, but their cost was high and even at the end of the Great War they were poorly designed and never satisfied British expectations. This is illustrated by Armistice demands that Germany deliver one Zeppelin airship to Britain and another to the USA as a part of their war reparations. Just as the Gemman jet aircraft were dissected in 1945, Zeppelin technology was analyzed after the Armistice.

Post War

The British did little more with rigids after WW I. They built a few more designs, induding one for the US, R-38 (renumbered ZR-2 by the US), which showed the failure of the British to successfully apply Zeppelin technology. Its structure proved to be weak, and it broke up in the air on irs fourth flight, in 1921, killing 44 people. Its loss, along with postwar cutbacks, spelled the death of the British airship program.

The US Navy, and to a lesser extent, the US Army, were also interested in airship design after the war. They bought German and British technology as well as building experimental craft themselves. Budget cutbacks quickly forced the Army to transfer its craft to the Navy, but the Navy kept on looking at the wide Pacific and Atlantic and remembering its coast-defense mission.

France and Italy were also involved in post-War airship development. Like Britain, both suffered airship disasters with great loss of life. The French Dixmude was lost and the Italian Roma in 1922 and European development of airships was abandoned.

The cost and technology of rigids was demanding, and only the US had helium. Using it meant only 80% of the lift of hydrogen per equivalent volume of gas, but safety was infinitely improved. Germany, for political reasons, kept on in spite of the hazards of using hydrogen, but Hindenburg's loss ended the German program. In any case, the interwar German program was exclusively civilian. The reborn Luftwaffe was not interested in anything as vulnerable as a hydrogen-filled airship.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s the US Navy's airship program was expanding. While not completely accepted by all parts of the Navy, the public and Congress accepted them as a valid and exciting military platform. One base, Lakehurst, New Jersey, was operating, and a second, at Sunnyvale, California, was under construction. Several large rigids had been bought or built, and the future looked bright.

Losses

Then came the loss of Macon, after Akron, which came in after Shenandoah. The only American rigid airship which was not a catastrophic loss was USS

Los Angeles. The Navy program was closed down.

Then came the loss of Macon, after Akron, which came in after Shenandoah. The only American rigid airship which was not a catastrophic loss was USS

Los Angeles. The Navy program was closed down.

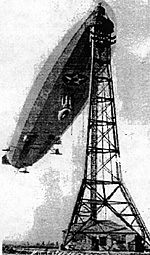

At right, the USS Shenandoah moored to the high mast at Lakehurst, New Jersey.

It revived, surprisingly, in WW II. The pressing U-boat threat forced innovation and solutions that might have been ignored in a less desperate situation. Blimps were developed as

ASW patrol ships, and like their British cousins in the Great War, served well. Hundreds of K-Type and later M-Type blimps were built. Equipped widh radar, MAD, and later in the war, homing torpedoes, they accounted for several U-boats and patrolled both coasts of the USA. US

blimps did not serve overseas, and no other country operated LTA craft in WW II.

In WW I, both British and German airships were most effective as maritime patrollers. The Germans had few convoys to escort, but the British found airships valuable in that

roll.

On patrol missions, airships would fly long missions, often over 24 hours, sometimes close to enemy coasts. Occasionally, they would encounter enemy fighters, which always resulted in the airship's loss.

The US Navy included airships in exercises throughout the late '20s and early '30s. The addition of scout planes in Akron and Macon allowed their search coverage to be dramatically increased.

There was no intention or desire to use the airships' Sparrowhawk aircraft offensively. Although the planes carried machine guns, this was for self defense, or the defense of the

mother ship. Deliberately seeking enemy aircraft with the planes meant

that the enemy craft would be in striking range of the mother ship, risking its loss, along with the loss of its entire air group. Also, they coult not carry large enough bombs to make an effective attack on surface ships, even if the mother ship could carry the payload.

Typically, the airship would be assigned an area to search. If the weather allowed, it would launch its planes and then try them in line abreast formation, sweeping a tremendous area of ocean visually. Even if the planes could not be launched, or it didn't have planes, it could still fly a racetrack or a variety of search plans to cover the area. The multiple man crews meant several lookouts searching, and a good chance of spotting anything in visual range.

BTTactics

Back to The Naval Sitrep #10 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1997 by Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com