Part II: The Battle Joined

The French general gave the orders for his troops to deploy for battle. Since the Ulm-Heidenheim Road passed through Albeck and was his line of communication, Dupont decided to protect this route by anchoring his left flank on the small village of Haslach. The main road passed through Haslach, in front of which Dupont posted his best line regiment--the 32nd Ligne under Colonel Darricau, along with the brigade commander, General Marchand. To the right of the two battalions of the 32nd was the company of foot artillery. Two 4-pounder guns and four 6-inch howitzers were unlimbered across the Ulm-Heidenheim Road. To the right of these pieces were General Rouyer with Colonel Meunier and both battalions of the 9th Legere.

Deployed as the second line of the division was Colonel Barrois' 96th Ligne. The horse artillery and light cavalry protected the left flank of the division. Two 8-pounders manned by the horse artillerists were on a small rise to the left of the 32nd Ligne, and served as a link between the infantry and the 1st Hussars positioned to the left of the guns. To properly shelter these horsemen until it was time for them to close with the enemy, the light cavalry were positioned in dead ground that offered them protection from Austrian cannon.

Dupont finished his reconnaissance

and realized that the key to his defensive position

was his right flank...

The right flank of the division was protected by two woods west of Haslach. The smaller of the woods, which was named "Kleinen Gehr," was approximately five acres in size and located between Haslach and another small village named Jungingen. Some 650 yards to the north of Kleinen Gehr was the larger wood, called "Grossen Gehr." The area between the two woods consisted of fields and meadows, and it was this avenue along which any direct movement between the two villages would be conducted. Finally, Dupont posted General Sahuc and his brigade consisting of the 15th and 17th Dragoons behind the 96th Ligne to act as the reserves for the French force.

While these regiments were shaking out for battle, Dupont finished his reconnassaince and realized that the key to his defensive position was his right flank, which offered the Austrians a broad avenue of attack that they could easily traverse. That axis of advance was also the weakness of the French position. The division's right flank rested near the Grossen Gehr, but the entire position was untenable unless the French also held the village of Jungingen some 2,200 yards west of Haslach.

Between Jungingen and Haslach, a small rivulet and Kleinen Gehr restricted the approach to either village. If the Austrians controlled Jungingen, they could freely direct troops around either the Kleinen Gehr or the Grossen Gehr to attack Dupont's right flank or rear as other Austrians assaulted Haslach from the front. Dupont reasoned that he might be able to buy some valuable time by forcing the Austrians to first capture Jungingen before initiating a full-scale attack on Haslach. Also, while busy attempting to capture Jungingen, the Austrian infantry would be susceptible to counterattacks.

For Dupont, the danger in posting any troops in Jungingen was that the distance from Haslach to Jungingen was going to make it difficult to properly support any men holding in the latter village. Since Jungingen had to be held in order to maintain the Haslach position, Dupont committed his small command of six battalions, three cavalry regiments and eight pieces of ordnance to a paper-thin defensive line that stretched along an 1.2-mile front (as compared to a normal frontage for a division of this size would have been half a mile or less)!

Therefore, in order to give his troops a chance to repulse the anticipated Austrian attacks and because Jungingen was critical to his position, Dupont decided to employ a version of the strong-point defensive scheme.

The Strongpoint Defense illustrated with maps and dioramas.

He ordered the village of Jungingen to be garrisoned with an ad hoc battalion of converged elites. To accomplish this, the grenadier and carabinier companies from Dupont's six battalions were quickly brought together to form a new battalion and placed under the command of chef de bataillon Decouchy from the general's staff and were hustled off to Jungingen. If the Austrians did not properly coordinate their combat arms in trying to expel the garrison of Jungingen, Dupont would not hesitate to commit reinforcements to that front to conduct local counterattacks.

While Dupont was putting up a brave front by deploying his men for battle, Mack was wasting no time with his arrangements for the destruction of the unwelcome visitors. From the parapet of one of the redoubts on the Michelsberg, Mack viewed the surrounding countryside. He did not detect any French troop movement along the south bank of the Danube, but could not see if more French were behind Dupont and arriving from the north on the Ulm-Heidenheim Road. With no immediate threat from the south, Mack could commit as many of his troops as he wished to the attack on the north bank. The Austrian general had available for battle a total of 11 regiments of infantry, four regiments of cavalry, plus more than 30 pieces of mobile ordnance with more than 100 heavy guns in position on the Michelsberg.

Completing his plans for battle, Mack decided to divide his troops into three columns. Ferdinand and Schwarzenberg would command the two left columns while Riesch and Werneck jointly led the right column. The latter column was closest to the Danube and consisted of seven infantry regiments. In the front line, Riesch and Werneck placed four regiments, each fielding three fusilier battalions for a total of 12 battalions. From right to left were Kolowrat-Krakowsky IR#36, Karl Riese IR#15, Reuss-Plauen IR#17 and Stuart IR#18.

In the second line, acting as reserves for the entire Austrian force, were 14 battalions of three regiments, namely: Manfredini IR#12 with four battalions of fusiliers and one battalion of grenadiers, Auersperg IR#24 with four fusilier battalions and one grenadier battalion, plus Erbach IR#42 that had three fusilier battalions and one grenadier battalion.

The two left-hand columns under Schwarzenberg and Ferdinand consisted of the infantry from regiments Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 with three fusilier battalions, Erzherzog Rainer IR#11 with two fusilier battalions, Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20 with three fusilier battalions and Froon IR#54 fielding two fusilier and one grenadier battalion.

Supporting these 11 battalions of infantry were six squadrons from the Kčirassier-Regiment Erzherzog Albert #3, and eight squadrons each from the Kčirassier-Regiment Mack #6, the Chevaulegers-Regiment Latour #4 and the Chevaulegers-Regiment Rosenberg #6. Therefore, Mack's force at Haslach-Jungingen totaled some 23,000 combatants, with the 37 battalions of infantry numbering 20,000 officers and other ranks, the 30 squadrons of cavalry mounting 2,100 people and 900 artillerists and train personnel serving 30 pieces of ordnance.

Although Mack enjoyed a significant advantage of numbers and total pieces of ordnance, his only mobile unit was one cavalry battery of six pieces present with the left-hand columns. The remaining 24 guns served as battalion pieces--far fewer than the 74 pieces that were theoretically supposed to support the movements of 37 battalions of infantry. Only 24 battalion guns were ready for action on 11 October because there were not enough healthy horses to pull all the pieces. The remaining guns were left on the Michelsberg.

As conceived, Mack's plan of attack would have met Frederick the Great's approval. The right column under Count von Werneck and Count von Riesch was to deploy between Orlingen and Bofingen, advance north from the Michelsberg and pin the enemy by attacking him in front of Haslach. Meanwhile, Mack would accompany the two left columns under Archduke Ferdinand and Prince Schwarzenberg. These troops, which included all the cavalry on hand, would move north to Jungingen, then wheel into a position facing east from which they would make a Frederickian style oblique attack on the French right flank. If all the Austrian formations could be properly coordinated, Mack reasoned that the French simply did not have enough men to be able to resist such an onslaught.

Apparently opposed by only skirmishers holding the key village, the two leading Austrian regiments halted, deployed their six battalions into line and advanced into Jungingen, driving the elusive tirailleurs before them. As the tirailleurs withdrew before the onward moving formed ranks of Austrians, they continued firing into the whitecoated masses.

Battalion after Austrian battalion rushed the church in an attempt to gain entrance. Soon, Austrian corpses began to litter the ground as their sacrifice to break into the church proved to be in vain. Unable to demolish the doors, the Habsburg infantrymen swirled around the church's stone edifice as the French grenadiers and carabiniers poured a deadly fire into the growing masses of assailants.

Ensconced in the village fighting at Jungingen, the Austrian infantry was not aware that the Austrian cavalry had failed to support their movements. Instead of advancing outside the village to protect the infantry's flanks, those in command of the Austrian cavalry chose to hang back, waiting for their comrades to emerge victorious from the village, and thereby resuming the advance against the French right flank. This lack of support would prove to have negative consequences for the Austrian infantry.

At right, the three different uniforms worn by the Austrian fusiliers during the 1805 campaign. Sketches © Andrew J. Arno

At right, the three different uniforms worn by the Austrian fusiliers during the 1805 campaign. Sketches © Andrew J. Arno

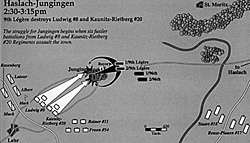

With Mack urging his men on, the two left columns got moving about 2:00 P.M.--long before Werneck and Riesch could get their right column underway. The infantry of the left columns was spearheaded by the three fusilier battalions from Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 and three fusilier battalions of Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20. As the Austrians moved towards Jungingen, they were met unexpectedly by an annoying fire from French tirailleurs on the edge of the village. These skirmishers were from Decouchy's converged elite battalion that, unknown to the Austrians, had already occupied the village church.

With Mack urging his men on, the two left columns got moving about 2:00 P.M.--long before Werneck and Riesch could get their right column underway. The infantry of the left columns was spearheaded by the three fusilier battalions from Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 and three fusilier battalions of Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20. As the Austrians moved towards Jungingen, they were met unexpectedly by an annoying fire from French tirailleurs on the edge of the village. These skirmishers were from Decouchy's converged elite battalion that, unknown to the Austrians, had already occupied the village church.

Entering the village, the Austrian battalions soon met the majority of the French elite battalion that had barricaded itself in the church. The church sits today on the same small rise in the middle of Jungingen, dominating the rest of the settlement. When the French ad hoc battalion of converged elites moved into this stronghold, sappers from the grenadier and carabinier companies fortified the structure by strengthening the doors and making loopholes through which the men could fire. Taking up positions inside the church, the French elites waited while the noise of battle grew louder and louder, the enemy finally reaching them shortly after 3:00 P.M.

Entering the village, the Austrian battalions soon met the majority of the French elite battalion that had barricaded itself in the church. The church sits today on the same small rise in the middle of Jungingen, dominating the rest of the settlement. When the French ad hoc battalion of converged elites moved into this stronghold, sappers from the grenadier and carabinier companies fortified the structure by strengthening the doors and making loopholes through which the men could fire. Taking up positions inside the church, the French elites waited while the noise of battle grew louder and louder, the enemy finally reaching them shortly after 3:00 P.M.

At right, French Grenadier officer in 1805 field uniform. Grenadiers were critical in Dupont's strongpoint defense at Jungingen. Sketch © Andrew J. Arno

At right, French Grenadier officer in 1805 field uniform. Grenadiers were critical in Dupont's strongpoint defense at Jungingen. Sketch © Andrew J. Arno

...the Austrian infantry was not aware that the Austrian cavalry had failed to support their movements.

From his observation point just west of Haslach, Dupont recognized the lack of coordination in the enemy's advance. The absence of Austrian cavalry on the flanks of Jungingen, coupled with the increasing haze of smoke enshrouding the village, was enough to convince him that the Austrians had failed to take the strong point and were ripe for a counterattack.

Leaving general de brigade Marchand and Colonel Darricau with the 32nd Ligne to cover Haslach, Dupont ordered general de brigade Rouyer and Colonel Meunier with both battalions of the 9th Legere to spearhead the assault. Colonel Barrois and the two battalions of the 96th Ligne were to follow in support of the light infantrymen. With each battalion's national color (lozenge pattern) as well as the 1801 pattern Revolutionary standard fluttered above the ranks, the 9th Legere hustled past Kleinen Gehr in attack columns. The battalions were abreast with the 1st Battalion on the right and the 2nd Battalion on the left. Turning west towards Jungingen, they used the woods to protect their right flank while the 96th Ligne followed in echelon, protecting their left.

Setting the pace for the advance of the 9th Legere was general de brigade Marie-Francois Rouyer. Rouyer knew that he was about to execute a counterattack that he and his men had repeatedly trained for in the mock battles at the Channel camp of Montreuil. Joined by his two aides, Captains Debaine and Bonrion, Rouyer and his staff rode along the line waving their swords and haranguing the men in shouts of "Vive l'Empereur!"

As a young man, Rouyer had served in the Austrian cavalry. With the coming of the Revolution, Rouyer quit the Habsburg army and entered French service as a captain of infantry. Faithfully serving La Patrie during the wars of the Revolution, Rouyer was promoted to general de brigade on 30 July 1799, and was made a commandant of the Legion d'Honneur on 14 June 1804, some seven months after he had reported for duty at Montreuil. During his 21 months in the Channel camp, Rouyer forged a close working relationship with the only regiment of his brigade and their colonel, Meunier. Both Meunier and Rouyer had received their promotions and assignments to Ney's camp in December 1803. The new arrivals became close friends and knew what to expect from each other.

Colonel Claude-Marie Meunier had been a distinguished captain in the chasseurs a pied of the Consular Guard when the colonelcy of the 9th Legere came open. Accepting the appointment, Meunier proved to be an excellent tactician, receiving praise from Rouyer, Dupont, and Ney. An exceptional colonel was a must for a regiment as celebrated as the 9th Legere. Famous for its exploits in the wars of the French Revolution in the campaigns of 1794, 1795 and 1796, the 9th demi-brigade Legere reached higher limits of glory on 14 June 1800. It was late in the afternoon of that day that the regiment counterattacked and threw the Austrian line into disorder immediately prior to Kellermann delivering his epic charge--two connected events that turned the Battle of Marengo into one of Napoleon's most famous victories. For this and their previous heroic accomplishments, Bonaparte gave the 9th Legere the title "l'Incomparable." As the fantassins of the 9th Legere approached Jungingen, Meunier knew that his men could not afford to stop and fire during a strong point defensive scheme counterattack. Before they moved out, Meunier ordered the light infantrymen to advance with unloaded muskets.

The sudden approach of two French battalions against a force approximately three times their own must have surprised the Austrian commanders. Unable to rapidly redeploy their battalions in order to receive the onrushing French light infantrymen, the Austrians were soon caught inside Jungingen between Decouchy's converged elite battalion holed up in its strong point and the counterattacking light infantry. Even with superior numbers, the disorganized Austrian infantry were no match for an adversary who had practiced time and again this exact scenario.

Preventing their escape by blocking their retreat routes from the village and then falling on their prey with the bayonet, the French light infantry first surrounded then cut to pieces the six battalions from Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 and Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20. Austrian companies surrendered en masse to the 9th Legere until more than 2,000 whitecoated infantry were captured by approximately 1,400 Frenchmen. Once these captives were started off towards Haslach, Rouyer and Meunier repositioned the 9th Legere in anticipation of receiving the next Austrian attack.

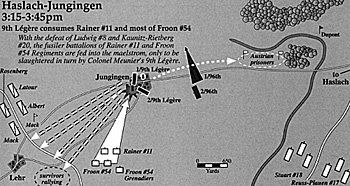

It was not long in coming. After losing more than 2,000 men from an approximate force of 3,300, the battalions from Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 and Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20 were finished for the day. As the panic-stricken survivors who managed to escape from Jungingen streamed back towards Austrian lines, Mack ordered up reinforcements in the form of Erzherzog Rainer IR#11 and Froon IR#54. Leaving the grenadier battalion of Froon in reserve, Archduke Ferdinand took the fusilier battalions of these regiments into the fray.

It was not long in coming. After losing more than 2,000 men from an approximate force of 3,300, the battalions from Erzherzog Ludwig IR#8 and Kaunitz-Rietberg IR#20 were finished for the day. As the panic-stricken survivors who managed to escape from Jungingen streamed back towards Austrian lines, Mack ordered up reinforcements in the form of Erzherzog Rainer IR#11 and Froon IR#54. Leaving the grenadier battalion of Froon in reserve, Archduke Ferdinand took the fusilier battalions of these regiments into the fray.

Five times the Austrians charged into Jungingen, pushing the tirailleurs before them and capturing all the village except the church. This strong point, tenaciously held by the Decouchy's elites, made it possible for the 9th Legere to counterattack each Austrian attempt to carry Jungingen. Despite Austrian numerical superiority in every assault, the well trained and expertly led French light infantry achieved success after success, resetting their defense each time to invite and await the next attack.

The French strong point defensive scheme at Jungingen turned the village into an Austrian slaughter pen, totally consuming Mack's infantry in his two left-hand columns. Habsburg losses continued to mount at an alarming rate with the repulse of each assault until Erzherzog Rainer IR#11 and Froon IR#54 had lost over 2,000 men following the repulse of their fifth attack. With the failure of the last attack by Erzherzog Rainer IR#11 and Froon IR#54, it appeared to General Rouyer that only one more Austrian infantry battalion--the grenadiers of Froon--was available to mount another assault against Jungingen. He therefore hastened to start his most recent captives towards the rear before the Austrian cavalry could make its presence felt or another infantry attack was mounted against Jungingen.

Part III: The Austrians Press the Attack

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #5

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com