Designer: Brien Miller

Designer: Brien Miller

Designer's Credits: Borodino, currently the only other game in the "Eagles of the Empire" series.

Number of Players: Designed for two, but can easily be played solitaire.

Playing Time: 2-6 hours

Complexity Level: Medium; experience playing wargames will help you start playing faster, but is not necessary to learn the rules. A little knowledge of Napoleonic tactics and history enables you to get more from the game.

Packaging: 1-inch cardboard box with a full color illustration of Russian Grenadiers advancing on the front, and a description of play plus counter and map samples on back.

Scale: Grand tactical with playing pieces representing divisions, regiments/brigades, or individual commanders.

Map: One 18-by-26-inch full color map, "geomorphically" divided into areas of varying size depending on terrain density (see sample of the map on page 24).

Playing Pieces: 380 cardboard playing pieces (or "counters"), 100 of which are large 1-inch rectangles representing major infantry, and 280 small 1/2-inch square counters representing leaders, cavalry, artillery, informational markers, and smaller formations of infantry.

Other Components: One 8-1/2-by-11-inch player aid card, an errata sheet answering some rules problems in the first edition, a six-sided dice, and a product registration card.

Rules: Two 16-page, 8-1/2-by-11-inch booklets, one with second edition "standard" rules for all games in the series plus designer's notes, and one with additional rules specifically for Friedland, plus scenarios, players notes, and research sources.

Not Included: Plastic ziplock bags can help sort and store the playing pieces.

Scenarios: Five, of which two are primarily meant to be used to learn the game system. Three are actual historical situations (including the two "training" scenarios) and two are "what-if" hypothetical scenarios.

Historical Background Information: Each of the scenarios is prefaced with fairly thorough background information. In addition, there is a partial research source listing, and a section containing general comments by the designer regarding the battle.

Publisher: Games USA

Publication Date: 1995

Stock Number: 1102

List Price: $35.00

Summary: Friedland is a moderately complex board game on the battle of the same name fought on 14 June, 1807 (the seventh anniversary of Marengo) between Napoleon's three-year-old Grande Armee and the Russians under General Bennigsen. The French Emperor finally achieved the decisive victory he had been seeking since the campaign of 1806 after a hard-fought, day-long battle. This success was the final undoing of the Fourth Coalition against France, and motivated Tsar Alexander to seek peace, formalized by the Treaty of Tilsit, leaving Napoleon master of most of Europe. The game accurately shows the difficulties the Russian commander operated under, and you will be hard pressed to defeat the French. Miller's design is innovative, utilizing a unique, variable-size area-style map for terrain/unit interaction. Through various mechanics, playing imparts a "feel" for the intricate combat and chain of command of the Napoleonic era.

Harold T. Parker, acknowledged as one of the premier scholars of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic period, wrote, "In the battle of Friedland everyone, including Napoleon, did his part, and everything clicked." It is curious then that this important engagement has been the subject of only two American board games among the many Napoleonic titles available. Except for a limited production by a now defunct small publisher in the late 1970s, Games USA's 1995 release is the only treatment of Friedland in a board game.

![]() The first things one notices in Friedland are the playing pieces. They are quite dazzling. The artist's use of color borders on extravagant, but with the wealth of information displayed for each unit or marker, they are quite functional as well.

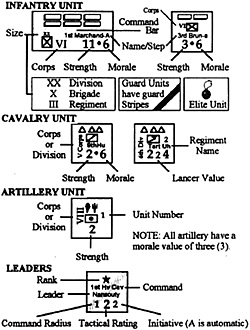

The first things one notices in Friedland are the playing pieces. They are quite dazzling. The artist's use of color borders on extravagant, but with the wealth of information displayed for each unit or marker, they are quite functional as well.

![]() Each counter has a stylized depiction of a particular unit's uniform, as well as a visual representation of the number of regiments remaining in that division or brigade. Other information includes a combat value, morale value, unit designation, elite or guard status, corps/wing subordination (a color bar), lancer value (if present), identifies artillery as light or heavy or horse, and (on large counters) a bisecting line to determine the direction the unit is facing. Although jammed with information, the playing pieces are presented in a fairly user-friendly fashion.

Each counter has a stylized depiction of a particular unit's uniform, as well as a visual representation of the number of regiments remaining in that division or brigade. Other information includes a combat value, morale value, unit designation, elite or guard status, corps/wing subordination (a color bar), lancer value (if present), identifies artillery as light or heavy or horse, and (on large counters) a bisecting line to determine the direction the unit is facing. Although jammed with information, the playing pieces are presented in a fairly user-friendly fashion.

Another item likely to catch the player's eye is the map, containing as it does, no hexagons. Unlike most board wargames which use a hexagon grid to determine placement, movement, and distance, Friedland's map was created using computer graphics and then divided into areas depending on terrain density. Natural chokepoints have been emphasized, as have large open areas where Napoleonic armies could easily deploy; the former denoted by making the area too small to physically fit a large counter. If a counter will not fit, it can not go into that area of the map, thus denying sections of the battlefield to the most powerful (and ungainly) units.

The area movement system in Friedland works well with the scale/size of units and helps players appreciate the limitations of linear formations and deployment distances inherent during this period of history.

The area movement system in Friedland works well with the scale/size of units and helps players appreciate the limitations of linear formations and deployment distances inherent during this period of history.

Delving into the rules it is immediately obvious that someone spent a considerable amount of time making them readable, understandable, and consistent. They utilize the so-called "case format" pioneered by SPI in the 1970s (rules are organized in major sections: 1.0, 1.1, etc.). Examples of play abound, their position in the rules book helps to avoid confusion.

Suggestion: Photocopy the sequence of play page, the close combat modifiers, and the cavalry charge pages from the rules book, as these are not adequately referenced on either the map or the player aid card.

Looking at the history presented in Friedland it becomes apparent the designer did some homework. Spot checks with sources in the EHQ library compared favorably with the order of battle and map in the game. The "what-if" scenarios enable the players to modify history, but these variations are plausible and, in some cases, help to equalize what can become a very uneven matchup.

Friedland does not follow the traditional I-move/you-move sequence of play. Instead, a number rolled on a die is used with an activation table. This die roll results in a player allowed to activate one or more forces. Activation means that units may move and/or attack, including a voluntary withdrawal. No activation = no movement, simulating slow, confused, or otherwise poor communication in the transmission of orders from one commander to another, and in the coordination of units under different leaders. The game demonstrates the battlefield reality that units under your command are not necessarily under your control; soldiers do not instantly obey and perform like robots to every order issued.

The biggest challenge for the Russian player is to overcome the tactical rigidity and sluggishness of his army. Can Bennigsen defeat Lannes' 5th Corps before Napoleon arrives with the rest of the Grande ArmŽe, or successfully withdraw his army intact and continue the war? Lack of activations frustrates these efforts. Plus, the Russian player can occasionally get a deactivation result: a force that might have been able to move and attack suddenly cannot.

Each leader counter gives their subordinate units full movement and combat capabilities if these units are within that leader's radius of command. To help clarify the chain of command, a diagram of each army's organization is printed on the map.

Each leader counter gives their subordinate units full movement and combat capabilities if these units are within that leader's radius of command. To help clarify the chain of command, a diagram of each army's organization is printed on the map.

Combat consists of artillery bombardment, infantry assault, and cavalry charges. Bombardment causes few casualties; the design reasons for this are unclear but at first glance it seems to be the game's one major historical weakness. A better use for artillery is to stack it with infantry and add its firepower to an assault. The French may form a "grand battery" with the right leader, as they did historically when General Senarmont orchestrated a decisive artillery "charge" which ripped apart the stubborn Russian battle line.

Assault involves totaling each side's strength and subtracting the defender's number from the attacker's, then totaling each side's morale value and doing the same, and finally subtracting the morale difference from the strength difference. Each player rolls a die and adds or subtracts modifiers such as tactical leadership, cavalry and artillery superiority, lancer bonus, etc., and then subtracts or adds the difference from their modified die roll to the strength/morale differential. This generates a number between -5 and +23, cross-indexed to yield a result in favor of either the attacker or the defender. It is not as complicated as it sounds and takes longer to explain than to execute.

Charges are not made during your own activation. Instead, cavalry that has not activated may charge an enemy force moving into or out of an adjacent area. Cavalry that is part of the activating force may counter-charge. Cavalry charges are handled exactly like assault combat described above except that the participating cavalry units must pass a morale check to initiate a charge.

The combat system forces opposing units back easily, but inflicting casualties is rare unless you have a significant advantage in numbers or push the enemy into an impassable obstacle (the Alle River). Friedland rewards the player that thinks in terms of maneuver rather than attempting to destroy the enemy with firepower and assault.

Another reviewer complained that since the battle was such a lopsided contest in which it appeared inevitable that Bennigsen's inflexible army would be thrown back into the river, the game is a waste of time. There are numerous games that heavily favor one side over the other and many are wonderfully challenging to play (as well as frustrating!). Additionally, various optional rules, such as limited intelligence, can balance the game. Friedland is a game where the outcome is never assured until the last activation is made.

Friedland's innovative game mechanics made for a highly competitive and tense simulation that can challenge both the novice and the experienced wargamer. It could also be used by miniatures gamers looking for scenarios for this battle.

Once the basics of the system are understood, the intuitive flow of the rules makes this a game easily learned but somewhat more difficult to master (the same could be said for real Napoleonic tactics). This reviewer enjoyed Games USA's design and looks forward to other titles in the series.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #5

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com