Aerial combat has been part of wargaming for a long time. There are many games on the market that simulate its various periods, but unfortunately when it comes to hard facts we often look to slick romanticised "history" books. Consequently our games have strongly dealt with the romantic notions of the "dog fight." There are many books that present a different picture. One of the most readable is "Fighter Pilot Tactics: The Techniques of Daylight Air Combat" by Mike Spick, published by Stein and Day in 1983.

Spick's book takes the reader through the growth of fighter tactics from WWI to the Falklands War. It deals with technical improvements as well as changing tactics and formations. It is that though it recognizes the importance of having a "hot" machine that factor does not dominate the book. In fact, superior tactical doctrine has won more battles for inferior airplanes than the "Tech guys" will ever like to admit.

The book walks through the wars of this century and shows how the participants evolved tactics to meet certain tactical problems. The intriguing thing to me is how the evolution is only half done when the war suddenly ends. By the time the next war comes many of the old lessons have to be relearned. Unlike in the slick histories it is made clear that there are no "perfect" tactics.

I strongly recommend going out and reading this book. It is fairly short, and easy to read. Unfortunately it is not in the book stores. Interlibrary loan may be the only way to get it. Since this is a hassle, the rest of the review highlights the lessopns I got from the book.

P101: Arm Chair Fighter Piloting

Oswald Boelke set down eight principles of air fighting in 1916.

- Try to secure advantages before attacking. If possible keep the sun behind you.

- Always carry through an attack when you have started it.

- Fire only at close range and only when your opponent is properly in your sights.

- Always keep your eye on your opponent, and never let yourself be deceived by ruses.

- In any form of attack it is essential to assail your opponent from behind.

- If your opponent dives on you, do not try to evade his onslaught but fly to meet it.

- When over enemy lines, never forget your own line of retreat.

- Attack on principle in groups of four or six. When the fight breaks up into a series ot single combats, take care that several do not go for one opponent.

These 8 rules can be further distilled into 2 rules. 1. Shoot the enemy when he is not looking, and 2. Don't let the enemy surprise you. The planes may have changed in 70 years but those 2 rules haven't. Not only do they remain true but they also play out to a statistic that was true in WWI and remains true today.

"Four out of every five pilots shot down never saw the person shooting at them."

If this is true then fighter tactics have a lot more to do with sneaking and observation than with swooping and fancy turns. This means that most wargames of the subject are missing the boat from an historical point of view. In fact the tactical doctrines that evolved in WWI were very much interested in seeing and not being seen.

A typical "Flight" consisted of 5 or 6 planes organized in a V or Vic formation. This had the

disadvantages of being easier to spot from a distance (the disadvantage of all formations) but brought the advantage of decreasing the chance of being "bounced" (i.e. surprised) since more people could be look out. It also made it possible for the leader to give signals to his men in a day before radios.

A typical "Flight" consisted of 5 or 6 planes organized in a V or Vic formation. This had the

disadvantages of being easier to spot from a distance (the disadvantage of all formations) but brought the advantage of decreasing the chance of being "bounced" (i.e. surprised) since more people could be look out. It also made it possible for the leader to give signals to his men in a day before radios.

As the Vic closed in around 100 yards (!!!) the lead plane (after taking careful aim) could open fire. More often than not that target would go down in flames. If the attacked formation still did not realize it was underattack, the leader might be able to shoot down another enemy. Once the attacker was spotted, the defender could choose to follow Boelke's advice and turn to meet the enemy (i.e. go into a dog fight), turn and run (which invites pursuit and death), or go into a defensive formation.

By 1917 the standard defensive formation was to form a circle. The "Lufbery" defensive circle

was the aerial equivalent of circling the wagons. Each plane covers the tail of the plane in front of it. At the same time the formation provides excellent visibility of the attackers. The obvious drawback is that this is not a very offensive formation.

By 1917 the standard defensive formation was to form a circle. The "Lufbery" defensive circle

was the aerial equivalent of circling the wagons. Each plane covers the tail of the plane in front of it. At the same time the formation provides excellent visibility of the attackers. The obvious drawback is that this is not a very offensive formation.

Bloody April 1917 saw the British throwing scads of undertrained pilots into the air to maintain "control of the air." It is true that many of them were shot down. They were, after all, mainly flying inferior airplanes. But formations like the Lufbery kept a lot of them alive and did win the control of the air for the allies.

If it came to a dog fight, the novice pilots often did not even realize what was going on. As the books describes it "they create a target rich environment for Aces." So if the defensive circle was broken then the new guys usually died. Even good pilots could get shot down if they were up against Von Richthofen. But in fact dog fights did not kill most people. They were too chaotic even for excellent pilots to follow. Kills happened in the pursuits that followed the madhouse, when the pilot is deprived of his flights to help him spot enemies.

Some people are born fighter pilots. They have the ability to keep track of who is where and what they are doing. This is very helpful in avoiding collisions, and lining up shots. But there are limits. Even the best pilots are hard put to keep track of more than 7 planes. And unfortunately it is the one you don't see that is the most likely to get you.

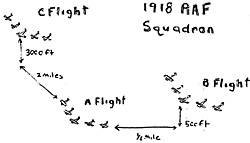

Towards the end of the war, Squadron level formations were turned out. Von Richtofen's Flying Circus consisted of 4 flights (6 planes each). By spreading out over several miles, this unit could surround an unsuspecting flight and annihilate it. If the flight turned to face any one enemy, it opened its rear to another.

British commanders actually began to discourage dog fighting in the last 6 months of the war.

They found that squadron formation (a sort of enlarged Vic) could provide greater security and

maneuver the enemy into unfavorable shoots.

British commanders actually began to discourage dog fighting in the last 6 months of the war.

They found that squadron formation (a sort of enlarged Vic) could provide greater security and

maneuver the enemy into unfavorable shoots.

Then the war ended.

Change of Tactics

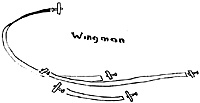

Airplanes got a lot better, but tactics did not change much until the Spanish Civil War. The Germans did not have enough Me 109s to use the old tactics so they came up with new ones. The presence of radios, decreased the need for the leader to be out front and visable. Instead 2 planes could fly abreast (with one keeping a look out over the other).

This looser formation of leader and wingman, was soon adopted by everyone and is still in use

today. Aside from increased ability to see, the two planes could support one another when they

were bounced.

This looser formation of leader and wingman, was soon adopted by everyone and is still in use

today. Aside from increased ability to see, the two planes could support one another when they

were bounced.

![]() The fighting pair could be formed into flights of 4 planes, and squadrons of 3 flights. As in WWI larger units could be organized into true air "battles." If not exactly like land battles, they did use all available terrain, and the formations they manuvered in were vital to success.

The fighting pair could be formed into flights of 4 planes, and squadrons of 3 flights. As in WWI larger units could be organized into true air "battles." If not exactly like land battles, they did use all available terrain, and the formations they manuvered in were vital to success.

Radar natually increased the ability to plan battles but the fighting still had to wait until visual contact was made (maybe 2 miles out, but often much closer). In fact even today, despite all our technology, most jet fighter combat still takes place within visual distance of one another (this is not to say they can't shoot the missile from 15 miles out, but are you certain that isn't one of our guys?).

I could go on from here but the book really explains the subject much better than I do. So, if you are interested in the type of information set out above, then try out "Fighter Pilot Tactics."

Up to this time, games have looked extensively at the dog fight side of air war. Some games have looked at strategic bombing and air defense but I don't know of any games that look at this middle ground. It looks as though there is some real fun that could be had in fighting out squadron and multisquadron level fights. It looks like a worthy project.

Back to MWAN #53 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1991 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com