The key problem faced by solo wargamers is to create a "thinking" enemy. The usual answer is to "automate" one of the sides This is easily done when the enemy has few options (perhaps defending a fortification) or the enemy has an uncomplicated plan (fuzzy wuzzies attacking head on despite the odds.) This article addresses programming a rational enemy. I do not claim to have it entirely figured out but I offer a methodology that works for me. As an illustrative example I submit the Battle of Chippewa, fought on 5 July 1814 on the banks of the Niagara River in Upper Canada.

Historical Campaign It was the third year of the war and the United States was no closer to seizing Canada. With the defeat of Napoleon, the President expected the British to transfer thousands of Peninsular veterans to North America. Before this happened, the Americans made a final attempt to invade Canada.

On 3 July Major General Jacob Brown took his Left Division across the Niagara River from Buffalo and seized Fort Erie. He then sent Brigadier General Winfield Scott's 1st Brigade north towards the next British position behind the Chippewa River. All day on the 4th, Scott was slowed down by Lieutenant Colonel Pearson's ad hoc battalion of light companies, dragoons, Lincoln militia, and allied Indians. That evening, Scott camped his brigade on the south side of Street's Creek about two miles from the British entrenched camp at Chippewa.

On 3 July Major General Jacob Brown took his Left Division across the Niagara River from Buffalo and seized Fort Erie. He then sent Brigadier General Winfield Scott's 1st Brigade north towards the next British position behind the Chippewa River. All day on the 4th, Scott was slowed down by Lieutenant Colonel Pearson's ad hoc battalion of light companies, dragoons, Lincoln militia, and allied Indians. That evening, Scott camped his brigade on the south side of Street's Creek about two miles from the British entrenched camp at Chippewa.

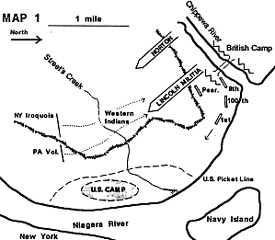

The Battlefield (See map 1) The battle was fought on the flat ground between the unfordable Chippewa River and Street's Creek. The ground closest to the Niagara was meadowland and partitioned at intervals by rail fences. About three-quarters of a mile from the river line lay a primeval woods, dense and cluttered with fallen trees. A tongue of woods, three or four hundred yards wide, stretched to within a quarter mile of the Niagara thus forming a defile in the middle of the otherwise open ground. The bridge to the British camp was protected by a tete-de-pont, an earthen parapet perhaps ten feet high and less than fifty yards long.

The Battlefield (See map 1) The battle was fought on the flat ground between the unfordable Chippewa River and Street's Creek. The ground closest to the Niagara was meadowland and partitioned at intervals by rail fences. About three-quarters of a mile from the river line lay a primeval woods, dense and cluttered with fallen trees. A tongue of woods, three or four hundred yards wide, stretched to within a quarter mile of the Niagara thus forming a defile in the middle of the otherwise open ground. The bridge to the British camp was protected by a tete-de-pont, an earthen parapet perhaps ten feet high and less than fifty yards long.

Preliminaries. Late in the evening, Brown arrived in camp with Eleazar Ripley's 2d Brigade. The next morning, the British commander, Major General Phineas Riall, sent a group of western Indians to reconnoiter and harrass the American camp. Riall was unaware that Fort Erie had fallen and he drew the erroneous conclusion that this body of troops was merely the American advance guard. He decided to strike and destroy the Americans. But first he would secure the forest so as to protect his right flank as he advanced.

Brown did not plan to attack before the 6th. As his third brigade arrived in camp that afternoon, he ordered it to clear the forest of Indians. The 3rd Brigade was commanded by New York militia Brigadier General Peter B. Porter. The brigade consisted of Pennsylvania volunteer infantry, a troop of mounted New York riflemen, and a group of New York Iroquois under their venerable leader, Red Jacket. Porter formed the natives and Pennsylvanians, about 850 in all, in a long single file. He marched the men into the forest where each man faced right. Now, with Indian scouts forward, the slender line walked toward Street's Creek. Porter was backed up by a single company of regular infantry from Ripley's brigade.

The Battle: Behind the creek, which was fordable everywhere in the forest, were a hundred western Indians who put up a short but stubborn fight before retreating. As Porter moved northward, all semblance of order dissolving. Pearson pushed the Lincoln militia (about 110 veterans of several fights) and about 200 of John Norton's Grand River Iroquois into the forest to confront Porter. Pearson retained his three companies of light infantry in line outside of the forest.

Porter's men pushed through the Canadian militia and Iroquois allies who put up a determined but unsuccessful defense - larger numbers told. Porter's brigade arrived piece-meal at the nonh edge of the forest where the Indians and Pennsylvanians were met by several volleys from Pearson's light infantrymen. Porter's brigade, although taking few casualties, could not stand and routed all the way back to their camp despite Porter's attempts to rally them.

Pearson moved southward slowly, keeping his battalion intact. Meanwhile, Riall was marching his two artillery companies and three line battalions across the bridge in column heading for the defile. Brown, positioned near the Street's Creek bridge, could only see the dust rising, above the tongue of woods. He was astounded that Riall would come out from behind his earthen parapets and he ordered Scott to meet and fight the British on the plain. He held Ripley in reserve in camp.

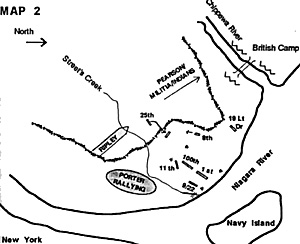

Scott sent his three battalions across the Street's Creek bridge (See map 2). He put a battery of three 6# guns on his right at the edge of the Niagara. Scott could see Riall's men coming through the defile in attack columns. He sent Jesup's battalion into the edge of the forest to secure his flank. He brought Campbell's and Leavenworth's battalions on line with a considerable interval between them. No sooner was Colonel Campbell on line when he was felled.

Scott sent his three battalions across the Street's Creek bridge (See map 2). He put a battery of three 6# guns on his right at the edge of the Niagara. Scott could see Riall's men coming through the defile in attack columns. He sent Jesup's battalion into the edge of the forest to secure his flank. He brought Campbell's and Leavenworth's battalions on line with a considerable interval between them. No sooner was Colonel Campbell on line when he was felled.

Riall posted two 24# guns and a howitzer on his left to cover his advance. He posted three 6# guns on his right. Campbell was replaced by Major McNeil. Riall put the Royal Scots and the 100th on line with the King's in reserve. Despite heavy cannon fire, Scott's men advanced in order. Riall, who saw their gray jackets and assumed he was confronting militiamen, realized his error. "Damn," he blurted out to John Hay, Marquis of Tweeddale, "these are regulars."

Both sides moved toward one another, firing as they did so. Scott ordered McNeil to throw forward his left flank. Thus the 100th, partially flanked, was marching into a fire trap. The Americans had loaded their cartridges with three buckshot and a ball. Their fast fire, and the added dispersion of their rounds, soon told. Brown ordered up another battery of three 6# guns which he positioned between NcNeil and Jesup.

In the forest, Jesup's battalion pushed Pearson's outnumbered men back. Then Jesup swung his men out of the woods and onto Riall's flank. Riall had ordered the King's to come on line but before they could, the Royal Scot's and 100th faltered and started to withdraw. Riall conducted a skillful withdrawal, his infantry covered by a troop of light dragoons and the royal artillery. His men further were protected by guns in the tete-de-pont as they withdrew over the bridge. The last soldiers over tore up the planking. Scott, in a major error, did not pursue vigorously. Brown had ordered Ripley to enter the woods, cross Street's Creek, and move through the forest parallel to the battle in order to get behind Riall and cut off his retreat. However, Brown issued the order too late and Ripley had barely crossed Street's Creek before the battle ended. Brown had 4000 men in his division although only 2100 were in the fight. Of these he suffered 325 casualties. Riall brought between 2130 and 2280 into the battle and lost approximately 500; the 100th alone suffering 204 casualties. The forest fight was particularly brutal. Nearly eighty bodies of Canadian militia and allied Indians were recovered and Red Jacket sold twenty prisoners to Porter, his brigade commander. In a few days, Brown maneuvered Riall out of position. The campaign continued at the Battle of Lundy's Lane and the Siege of Fort Erie.

The Solo Battle. To refight this battle, I chose to be Riall and attack. I then devised (automated) the Americans' defense. I followed these steps.

- Decide on starting positions for both forces.

- Identify decision points for the defenders.

- Construct courses of action at each decision point and probabilities that commanders would choose a specific course of action.

- Assign victory conditions.

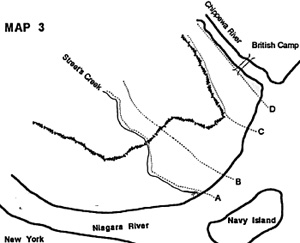

1. Starting positions Refer to map 3. I started the western Indians in the forest between lines A and B postured to receive an Arnerican attack. I put the Lincoln militia in the forest along line B. Pearson's light battalion and Norton's Iroquois were north of the forest between lines C and D. The British regulars were in the open area in column, with the head of the column coming even with the defile along line C.

1. Starting positions Refer to map 3. I started the western Indians in the forest between lines A and B postured to receive an Arnerican attack. I put the Lincoln militia in the forest along line B. Pearson's light battalion and Norton's Iroquois were north of the forest between lines C and D. The British regulars were in the open area in column, with the head of the column coming even with the defile along line C.

Porter's brigade was on line facing north with Red Jacket's men in the forest and Fenton's in the Opetl. His mission is to clear the forest of all enemy. Scott's brigade was in column with Leavenworth's battalion approaching Street's Creek bridge. Scott had not yet received orders. Ripley's brigade was guardillg the camp, awaiting orders.

Order of Battle for Chippawa, 5 July 1814

Decision Points. As you may have figured out, the lines A through D are decision points. The American brigades will dice tor a course of action as they arrive at a line. Brown could not find Porter in the woods once Porter left camp. Therefore Porter has his mission - to clear the forest - and will pursue that course as long as he can.

3. Courses of action. I thought through the historical battle and devised courses of action for Brown, Scott, and Ripley and then I assigned probabilities of their choosing one course over the other as they arrived at a decision point. Riall wanted to defeat what he believed to be the American advance guard before the rest of the Americans could intervene. Of course Brown did not know what Riall was up to and his courses of action mtlst retlect his ignorance.

Brown's first problem was to choose between fighting Riall along Street's Creek or on the plain. Historically, he needed to defeat Riall in order to pursue the campaign. He would rather fight him in the open rather than behind entrenchments. If Brown remained behind Street's Creek, Riall might not press the attack and instead return to his camp. Therefore, as Riall crosses line C, Brown has a 1 in 6 probability of ordering Scott to form a defensive line behind the creek and 5 of 6 of ordering Scott to decisively engage Riall on the plain.

If Scott crosses the bridge, he must decide on a formation. I assigned one company of three guns to support him. There is a 4 of 6 chance that Scott will form his brigade on line with battalions on line. There is 2 of 6 that he will put his battalions on line but keep his brigade in an attack column moving forward. Even odds as to which flank he will position his guns. If Scott gets to line C, there are 2 of 6 chances that he will stop on the line until supported by Ripley and 4 of 6 that he will push his attack. If Scott forces Riall to withdraw, odds are even that he will pursue vigorously up to and across Chippewa River.

The issues for Brown are wilen and how to commit his 2d brigade. Brown is unsure of Riall's intentions but will start the decision process once Riall and Scott open a fire-fight with muskety. Each turn that Scott and Riall fire at one another. I roll a die with 1 chance of 6 to order Ripley into contact. Ripley remains in camp ready to march until ordered. I devised three attack axes with even odds of Brown ordering one of them.

The first is across Street's Creek bridge in column and coming up on Scott's right. Once 300 yards from Riall, Ripley deploys his battalions onto line, one battalion behind the other at 200 yard intervals. He presses the attack staying alongside the Niagara River heading toward the defile. If Scott withdraws, Ripley tries to cover his retreat. If Scott has already withdrawn to the Street's Creek bridge. Ripley forms his men along the creek to cover the retreat.

The second course of action is for Ripley to wade the chest-deep creek and advance in column along the edge of the forest. He presses forward and cuts through the tongue of woods heading for the Chippewa bridge.

Ripley's third course of action is to move entirely inside the forest, out of Riall's view, again heading for the Chippewa bridge. Movement is slow, no more than half normal movement. Ripley keeps his men in a column, one battalion behind the next. Any of Porter's men withdrawing will have a fifty-fifty chance of rallying to Ripley. If there are British or natives in the forest, Ripley has 2 chances in 6 of forming his lead element on line before receiving enemy fire.

Now back to Porter. Once Porter makes contact, roll the dice to see how many groups his brigade breaks into as they push forward. Add two to a six-sided die, tilUS splitting into a minimum of three and maximum ot nine groups. Each band will press the fight and will orient on the closest enemy Any band which crosses line B and is not in contact with the enemy, has a 3 in 6 chance of remaining on line B until hearing gunfire at which time the band will move toward the closest fire.

As Porter's men arrive at the edge of the forest at line C, they will have accomplished their mission. As each band arrives on line C, it has a 50-50 chance of consolidating with the first band to arrive. Once the band with Porter arrives, roll a single die. Odds are even that he will try to attack the tete-de-pont. Any of his men who can see him do this will join the attack.

When the Americans arrive at an event which should prompt a decision; devise two or more options and roll the die. For example, when Scott saw Porter's men fleeing the forest he assumed that his flank was no longer secure and he threw Jesup into the woods to cover the brigade.

4. Victory conditions. I based these conditions on an analysis of the historical conditions.

-

Decisive British - Americans withdraw from their camp.

Marginal British - Americans driven behind Street's Creek.

Decisive American - British destroyed, Americans cross the Chippewa.

Marginal American - British driven across the Chippewa.

Conclusions. This methodology can be applied to many small historical battles with reasonable results. I chose a battle in which the "automated" side had only three maneuver units and one of these (Porter) had orders that carried him through to the end of the battle. I resisted sending battalions off on independent missions but I suspect I could have without too much dilliculty Would this methodology work with a large number of maneuver units, perhaps six or more? I don't know.

Some final thoughts. Keep orders simple, perhaps sketching attack axes rather than writing out detailed orders. The only right way of doing things is your way. Have fun! Remember the stirring motto of the REMF's solo wargaming club - "I'd rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy."

Selected Bibliography for the Niagara Campaign of 1814.

Berton, Pierre. Flames Across the Border: the Canadian-American Tragedy, 1813-1814. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1981.

Graves, Donald E. The Battle of Lundy's Lane. Baltimore: the Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1993.

Kimball, Jeffrey. "The Battle of Chippawa: Infantry Tactics in the War of 1812." Military Affairs (now called the Journal of Military History). Volume 32. Winter 1967-68. pages: 169-186.

Whitehorne, Joseph. While Washington Burned: the Battle for Fort Erie, 1812. Baltimore the Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1992.

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior 115

© Copyright 1996 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com