The EE&L Staff will be happy to answer questions and share comments and answers or answers on uniforms, tactics or other subjects. All such material should be sent to the Editor: Jean A Lochet (Mr.), 4 Kelly St. Metuchen, NJ 08840.

QUESTION 11-2:

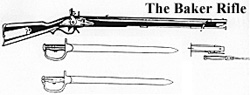

I have a two-part question concerning the British Baker Rifle sword bayonet.

(1) What year was the knuckle guard added to the hilt of the sword bayonet? I have a print and figure of the experimental Rifle Corps without the knuckle guard, circa 1803.

(2) Was the slot on the hilt which slid onto the bar on the rifle barrel on the left side of the handle or on the top of the hilt? I'm not able to determine if the handle was parallel (side mounted) or perpendicular top mounted) to the barrel.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 11-2:

We don't know when the knuckle guard was added to the hilt of the Baker Rifle sword bayonet. Although we don't have primary sources available to answer at least one of the two questions above on the Baker rifle, we can make an educated guess.

From the several available drawings we have on hand, we are able to say that the sabre-bayonet was apparently fixed on the right side of the rifle by the spring mechanism shown in the adjacent drawings. The very same drawings also suggest that the slot was on the left side of the hilt rather than on the top of the hilt.

The Baker rifle was a very successful weapon but other types of rifles were also used

by the Continental powers with various degrees of success.

The Baker rifle was a very successful weapon but other types of rifles were also used

by the Continental powers with various degrees of success.

The rifle was German in origin and the military version originally were privately owned weapons used by the huntsmen and gamekeepers formed into specialist Jager (sharpshooter)

units. Rifles differed from the smoothbore musket in that their shorter rifled barrel had a series of grooves which imparted a spin to the bullet as it was fired, increasing both the

accuracy and the practical range. Continental rifles, unlike muskets, had a back and

foresight. The muzzle loading rifle was loaded in the same way as a musket except that the

lead bullet was patched with a disc of greased felt, wool, cotton or leather to ensure the

greatest contact with the rifling. The bullet had to be forced down the barrel with

ramrod and even mallet. Loading a rifle was a time-consuming business. Scharnhorst

[1] the well known Prussian general and reformer, found,

"... in an analysis of tests carried out with Prussian rifles under his supervision, that its registered on small target by rifles compared 2 to 1 with those registered by muskets at 160

yards, and 4 to 1 at 240 yards. On large targets the proportions were 4 to 3 at 160 yards, and 2 to 1 at 300 yards.... The times needed for loading, aiming and firing were 5 to 2 as between the rifle and musket at 160 yards, and 5 to 1 at 240 yards."

Scharnhorst concluded that the "... Rifle and musket have about the same effect in the same

period of time; but the musket needs three to four times as much ammunition as the rifle.

Furthermore, under enemy fire a Jager is more liable to aim than an ordinary infantryman

because he is convinced that without aiming he never hits at all...."

Peter Paret [2] further concludes from these figures that:

"In any system of tactics that did not rely mainly on massed, unaimed fire, the rifleman was at least as effective as the musketeer. He was at a disadvantage only when heavy small arms fire was called for to repel a charge at close quarters."

Greater use of rifles in Continental armies was inhibited by the lengthy manufacturing process required and the higher cost, as a rifle was about fifteen times more expensive than a good musket.

Hunting rifles were used throughout the Napoleonic Wars, especially in Prussia and other small German states. Some German units from the Confederation of the Rhine serving with the French carried rifles. Rifles never found wide use in the French army but the famous carabine de Versailles [3] (a rifle) was issued only to selected officers and NCOs of the light infantry and was of ficially withdrawn in 1807. However, both the Versailles rifle and the cavalry rifle Model 1793 were still in very limited use as late as 1812.

As mentioned above, the greatest disadvantage of the rifle was its slow rate of fire which was a serious handicap in repelling a charge at close quarters. Using ordinary cartridges with the rifle changed the rifle to an ordinary musket, increasing the rate of fire but decreased the accuracy which was not important at close range.

In the early Wars of the French Revolution and Empire, the Austrians overcame the difficulty by using a double-barrelled short musket, the upper barrel rifled and the lower smooth-bored to allow more rapid loading. In 1779-80, an unusual rifle was introduced. It was the Girardoni air rifle 20-shot repeater which was issued to Jagers in 1792 to 1799. However, the difficulty of maintenance in the field and the death of its inventor led to its withdrawal in 1800. Several newer weapons, the 1795, 1798 and 1807 rifles, were introduced in the new

Jager battalions (only the third rank was equipped with rifles; the other two ranks were equipped with short muskets). The 1807-pattern rifle resembled the Baker rifle [4] and also included a sabre-bayonet.

In 1787, the single regiment of Jagers in the Prussian army was equipped with the 1787

pattern rifle. The weapon was not originally equipped with a bayonet or a patch-box but the newer version adopted in 1810 had both. That new type of rifle was issued to several Prussian light infantry units in the 1812, 1813, 1814 and 1815 Campaigns. The means of fixation is shown on the enclosed drawing 5. (See the picture showing the action of some Silesian Schutzen at the Battle of Etoges in 1814 on page 27).

The Russian army also used rifles. No less than eleven types of muskets were in

service. Twelve rifles were issued to the best marksmen of the each Jaeger company and sixteen per squadron of Cuirassiers and Dragoons.

The article on the Baker rifle published in the Alamo Journal, issue 93,

mentions that when the Baker rifle was fired with the sabre-bayonet attached "the muzzle blast strikes under the crossguard and grip with such a force that after only a few shots the mechanism would be damaged so severely that the bayonet would no longer stay on the rifle."

That may very well have been but we do not believe that the Baker rifle was fired with the sabre-bayonet fitted except in emergency situations such as repelling a cavalry charge. Light infantry units equipped with the Baker rifle were not expected to be involved in close action and were very seldom engaged in such combat. Precisely because of their inability to deliver fast fire, Bismarck mentions that the inherent weakness of rifle-equipped units was their vulnerability in such situations. That was overcome with the Baker rifle and later Continental versions of rifles.

"British and KGL riflemen had a weapon which was quite different from those made on the Continent. The Baker rifle could deliver both accurate slow fire and also musket-type, relatively fast fire. If a bullet was carefully patched and forced down the bore, it could be shot precisely. If a regular paper cartridge, 'carbine' size, was used with the bullet unpatched, loading was almost as fast as with the musket. The 95th, the KGL light battalions and the light companies of KGL battalions were armed with these rifles at Waterloo. They were effective with both types of loading, depending upon whether speed or accuracy was required."

[1] Scharnhorst Uber die Wirkung des Feuergewehrs

Berlin, 1813, p.96, translation to be found in Peter Paret's Yorck and the Era of Prussian

Reform, Princeton University Press, 1966, p.271. Question 1: Battle of Talavera Order of Battle (French) Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents #11 The advantage of the Baker rifle was that it could be fired as a musket. The following is what Jac Weller says in Wellington at Waterloo on page 174:

The advantage of the Baker rifle was that it could be fired as a musket. The following is what Jac Weller says in Wellington at Waterloo on page 174:

[2]See Peter Paret's work.

[3] The French word carabine means rifle. The rifle, Model 1793, went through many transformations, the last being the Corrected Year XII model.

[4] Philip Haythornthwaite Weapons and Equipment of the Napoleonic Wars. Blandford Press, Dorset, 1979. p. 25.

© Copyright 1995 by The Emperor's Press