Note from the Editor:

From time to time EE&L will publish articles covering the Wars of Frederick the Great, since they increase our understanding of the tactics used during the Wars of the Revolution and of the Empire. Note that Frederick's oblique order and oblique attack were used by the Prussian army during the Campaign of 1806.

I read with considerable interest the article on Frederick's Oblique Order by Marc Raiff in EE&L#4. I agree with Paddy Griffith and Christopher Duffy about the importance of studying

eighteenth century strategy, tactics, etc., in order to better understand Napoleonic warfare.

I read with considerable interest the article on Frederick's Oblique Order by Marc Raiff in EE&L#4. I agree with Paddy Griffith and Christopher Duffy about the importance of studying

eighteenth century strategy, tactics, etc., in order to better understand Napoleonic warfare.

Mr. Raiff's article is an extremely helpful effort toward a better understanding of the roots of Napoleonic warfare. I must, however, quibble with a few points in the article. While Mr. Raiff certainly has a working grasp of the nature of Frederick's Oblique Order, there are certain things that perhaps may be expounded. He rightly points out that Frederick's Oblique Order represented a rejection of the then common "attack along the entire front." This points to the heart of the issue of Frederick's Oblique Order and its uses, as the following will show. However, there are a few issues that first bear clarification.

Unfortunately, many people are somewhat confused about just exactly what the Oblique Order is, and how it differs from and works with other aspects of Frederick's tactics. This article will to try make these distinctions a little more clear, although, as the history of Frederickian warfare is no less contentious than the Napoleonic, others will no doubt have perspectives differing from my own.

Part of the confusion about Frederick's tactics stems in part from semantics. Frederick's system is often described as an "oblique attack," implying that it was essentially a system

of advance upon the enemy. The EE&L #4 article tends to follow this lead, describing "the grand tactical ploy of Frederick's 'oblique attack' (as consisting) of two techniques: "march by lines" and "attack in echelon."

Part of the confusion about Frederick's tactics stems in part from semantics. Frederick's system is often described as an "oblique attack," implying that it was essentially a system

of advance upon the enemy. The EE&L #4 article tends to follow this lead, describing "the grand tactical ploy of Frederick's 'oblique attack' (as consisting) of two techniques: "march by lines" and "attack in echelon."

It is important to realize the distinction between the term Oblique Order and the oblique attack. (This may initially sound trifling, but it is absolutely essential to an understanding of Frederick's tactics.) Frederick himself refers in his writings to "my oblique order of battle" in many places. An order of battle in the eighteenth century was a schematic listing of the units of an army in the order of their deployment for battle. Because deployment touched upon the honor and prerogative of regiments and their commanders, staff officers drew up orders of battle to assign each unit a place in the battlefield deployment commensurate with its prestige or lineage, as well as its function. So, the oblique order of battle was the arranging of units in a certain fashion upon the battlefield. Thus, an oblique attack is made in an oblique order of battle. (Originally this involved withholding an entire wing of an army but was later refined to employ a deployment of battalions en echelon.)

This point may seem obvious enough, but much of the misperception about Frederick's Oblique Order stems from a confusion about the distinction between an arrangement of units within a deployment and the place of deployment and subsequent axis of advance. In other words, the Oblique Order is not synonymous with a flank attack.

A further word about flanks may be

in order here. Anyone familiar with

military history knows the importance

of flanks. Frederick himself writes, "It

is axoimatic that you must secure your

own flanks and rear, and turn those of

the enemy." [1]

Because of the growing emphasis on firepower, units in the latter seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries gradually were "flattened." The number of ranks dropped from twelve or more in the early Thirty Years War to six, then to four, and eventually to three by the time of the Seven Years War. (Some armies may have persisted with four ranks, notably the Russians.) As this trend continued, a unit's maneuvering flexibility declined and its flanks became more vulnerable. In the early Thirty Years War it was not uncommon for a unit's depth to equal its breadth, and units (the tercio, for example) were able to defend themselves from attacks on any side.

As a result of "flatter" units, generals adapted their deployments and maneuver to maintain the security of their armies' flanks. Hence came the rise of long lines of units, each itself in line, with small intervals between units. Cavalry units, infantry units deployed in squares or at right angles to the front, and terrain features were used on the extreme flanks to provide security for the flanks of the army itself. (Frederick was a strong advocate of the use of terrain to secure a flank, and we see this legacy in the Prussian army of 1806.) The army had to " attack along the entire front, " because an advance by only part of an army would expose those units to being flanked. But a simultaneous advance with one's entire army risked total defeat, since the bulk of the army was committed to battle and beyond

the commander's control.

One expedient was the use of reserves. Reserves at this time were often a "third line" or other such body deployed in the rear. In the event of defeat, this force would plug any gaping

holes that occurred and would form the rearguard to protect their fleeing comrades. The idea of using reserves as a masse de rupture in the Napoleonic sense was virtually unknown. Since

the army already was deployed in line without usable intervals, there was no place for such a reserve to deploy and strike. (Hohenfriedsberg is an exception to this and occurred because the 6th Prussian Dragoons were deployed in the middle of the Prussian lines rather than on a flank, as was custom.) Likewise, to disengage a portion of one's army to make way for such an attack

again risked exposing the flanks of remaining units in the front line.

This was particularly true in Frederick's time. Armies in the eighteenth century were brittle instruments. Infantry battalions had evolved into walking batteries whose

function was largely to bring the highest volume of fire possible upon the enemy.

This is why Prussians were extensively drilled to fire quickly. Frederick toyed

with the idea of advancing his infantry without firing, but he gave this up as

too expensive in manpower and impossible to achieve in the face of a steady enemy, especially artillery.

This was particularly true in Frederick's time. Armies in the eighteenth century were brittle instruments. Infantry battalions had evolved into walking batteries whose

function was largely to bring the highest volume of fire possible upon the enemy.

This is why Prussians were extensively drilled to fire quickly. Frederick toyed

with the idea of advancing his infantry without firing, but he gave this up as

too expensive in manpower and impossible to achieve in the face of a steady enemy, especially artillery.

This was the dilemma facing eighteenth century tacticians. Viewed from this perspective, Frederick's solution seems all the more ingenious. His system allowed a commander to commit a portion of his forces, keeping the bulk of the army out of the canister range of enemy artillery, while not exposing the flanks of his advance elements. The withheld portions then could exploit a victory or cover the withdrawal if the advance elements were defeated. This technique neatly meets the requirements of Frederick's above mentioned axiom. Since the bulk of the army is kept in reserve until a decision is clear, it also lessens the requirement for a "third line" of reserves, which the smaller Prussian armies could ill afford.

This was the dilemma facing eighteenth century tacticians. Viewed from this perspective, Frederick's solution seems all the more ingenious. His system allowed a commander to commit a portion of his forces, keeping the bulk of the army out of the canister range of enemy artillery, while not exposing the flanks of his advance elements. The withheld portions then could exploit a victory or cover the withdrawal if the advance elements were defeated. This technique neatly meets the requirements of Frederick's above mentioned axiom. Since the bulk of the army is kept in reserve until a decision is clear, it also lessens the requirement for a "third line" of reserves, which the smaller Prussian armies could ill afford.

...attack was what the

entire Prussian army was

designed to do. That spirit

carried into the 1806 campaign.

Christopher Duffy, in his excellent The Military Life of Frederick the Great speaks of the Oblique Order in this way:

"Two principles appear to have shaped the Oblique Order. First there was the ambition to concentrate overwhelming force on a vulnerable point, which would render it possible for a small army like the Prussian to gain a local superiority.

"The second was Frederick's desire to exert the greatest possible control throughout the battle. [2]

An important note to make at this point is that Duffy speaks of concentrating on a vulnerable point. Obviously this includes an assault made from beyond an enemy's flank. Much of Frederick's own writings, as well as his battles, center on this type of enemy vulnerability.

Clearly then, the Oblique Order does not require the positioning of one's forces beyond the flank of the enemy.

However, this is not the only type of vulnerability the Oblique Order is designed to exploit. In his writings, Frederick describes a type of oblique attack upon a weakly-held enemy center and a concentration upon a flank when "it is impossible to surround that part of the enemy army that you desire to attack." [3] The treatise then outlines an Oblique Order attack made from the front of the enemy's position. Frederick even includes a plan drawing of such an attack. Of this he writes, "This plan... shows how I outflank the enemy left." [4] He goes on to describe how he masses his troops against one end (flank) of the enemy position, while olding the remainder out of danger.

However, this is not the only type of vulnerability the Oblique Order is designed to exploit. In his writings, Frederick describes a type of oblique attack upon a weakly-held enemy center and a concentration upon a flank when "it is impossible to surround that part of the enemy army that you desire to attack." [3] The treatise then outlines an Oblique Order attack made from the front of the enemy's position. Frederick even includes a plan drawing of such an attack. Of this he writes, "This plan... shows how I outflank the enemy left." [4] He goes on to describe how he masses his troops against one end (flank) of the enemy position, while olding the remainder out of danger.

The Duke of Brunswick

fought and lost in 1806

with the army designed

and built by Frederick.

Rather, it is a deployment and advance that allows one to concentrate upon a weak portion of the enemy position without either exposing one's own flanks or committing the bulk of one's army. Usually, this did involve a flank march to "surround that part of the enemy army you desire to attack," but Frederick saw this as a distinct issue, not as essential to his Oblique Order.

We can look to Frederick's own words for a summary of the Oblique Order. He writes:

"Doubtless you will have noticed that the constant principle I follow in all my attacks is to refuse one wing or engage only a detachment of the army with the enemy.... This disposition gives me the advantage of risking only as many troops as may seem appropriate, and if I notice some physical or moral obstacle in my way I am free to abandon my plan, pull back the columns of my attack into my lines, and withdraw my army, placing it always under the protection

of my artillery until beyond the range of enemy fire. The wing that has been nearest the enemy then falls back behind my refused wing, enabling the latter to support and cover me when I am

defeated. If then I defeat the enemy, this method enables me to achieve a more brilliant victory; if I am defeated, it reduces my losses considerably."[5]

That the Oblique Order was effective only in the attack seems obvious. Attack is what it was designed to do, and, in fact, attack was what the entire Prussian army was designed to do. That spirit carried into the 1806 campaign.

On a related subject, the Prussians of 1806 have been criticized for following the letter rather than the spirit of Frederick and his tactics. The argument seems unfair, since Frederick himself, especially in his later years, emphasized the letter of his instructions.

Duffy raises the issue that perhaps the usefulness of the Oblique Order had passed by the latter part of the Seven Years War, outmoded by new Austrian developments involving copious artillery and attacks by independent columns. (Some historians argue that Frederick attempted

something like this at Liegnitz.)

Frederick spent much of his later years attempting to refine his Oblique Order (unwilling to renounce it) to fit the evolving nature of the battlefield. This involved, in part, more elaborate deployments which were harder to control and maneuver. He also reformed the army, with less than spectacular results.

In response to the Austrians, Frederick was forced to deploy more artillery, which

he disliked as expensive and less mobile. (Hence, his experiments with horse

artillery as a way to achieve greater mobility for his guns.) Frederick also came

to rely more on artillery as the quality of his infantry deteriorated following the

bloodlettings of 1757 and 1758. He employed artillery as screens and, in more Napoleonic fashion, in masses to overwhelm a portion of the enemy position.

Frederick also saw the need to counter his enemies' light troops on the battlefield. In his early campaigns, Croats, Freikorps and other light troops were primarily involved in la petite guerre of outpost skirmishes, reconnaissance and the like. Using them to "soften up" an enemy was not common. In battle they normally guarded a flank or occupied terrain features which required more open deployments.

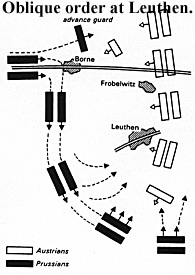

This fits nicely with Frederick's battlefield objective, i.e., to disrupt the plans and

dispositions of his enemy and to exploit the resulting confusion. (By the way, the brittle

nature of eighteenth century armies was one reason commanders were loathe to leave a good position, even when the opportunity for a pre-emptive assault or counterattack presented itself. This would upset the equilibrium of the army and strain a patently inadequate command structure, requiring more speed and flexibility than it could muster. When the Austrians noticed

Frederick's movements beyond their flank at Leuthen, they did not adjust their dispositions at first, though from our perspective that would seem a simple and prudent measure, something any wargamer would do. For the eighteenth century commander, re-deployment was a risky and urdensome undertaking. Of course, the nature of the command environment in the eighteenth century is worthy of study, as it underscores the importance of some of the innovations of Napoleon).

This fits nicely with Frederick's battlefield objective, i.e., to disrupt the plans and

dispositions of his enemy and to exploit the resulting confusion. (By the way, the brittle

nature of eighteenth century armies was one reason commanders were loathe to leave a good position, even when the opportunity for a pre-emptive assault or counterattack presented itself. This would upset the equilibrium of the army and strain a patently inadequate command structure, requiring more speed and flexibility than it could muster. When the Austrians noticed

Frederick's movements beyond their flank at Leuthen, they did not adjust their dispositions at first, though from our perspective that would seem a simple and prudent measure, something any wargamer would do. For the eighteenth century commander, re-deployment was a risky and urdensome undertaking. Of course, the nature of the command environment in the eighteenth century is worthy of study, as it underscores the importance of some of the innovations of Napoleon).

"We can shoot them up

ourselves if they fall back

or do not attack with

sufficient enthusiasm."

As the Austrians (tough for a Napoleonic buff to think of them as innovators) increased the role of light troops in the Seven Years War and War of the Bavarian Succession, Frederick began to realize that he needed a countermeasure. He was also looking for ways to counter the numerous and deadly Austrian artillery. He proposed sending forward open order bands of Freikorps as a kind of forlorn hope to drive off enemy light troops and absorb the bulk of the punishment from the artillery. Peter Hofschroer describes other solutions proposed by the Prussians in their regulations, though many were not effectively implemented before Napoleon stamped the army out of existence in 1806. Like the conservative Frederick himself, the Prussians often proposed innovations but proved less than enthusiastic about actually adopting them.

By the way, Frederick hated Freikorps, as one could guess from his idea of deploying them as a forlorn hope. In describing this use for them he says, "We can shoot them up ourselves if they fall back or do not attack with sufficient enthusiasm."[6]

In concluding his article, Mr. Raiff assesses what he sees as the weaknesses of Frederick's tactical system. He says it lacked depth, reserves and skirmishers in addition to being impossible to properly command.

From the foregoing, we can see that Frederick developed the Oblique Order to maximize control and increase the amount of reserves by holding most of the army out of contact. Lack of depth was not as important for an army deployed in this fashion. As to skirmishers, their bsence

had little to do with the Oblique Order. Rather it had a great deal to do with the nature of the Prussian society, its military machine and Frederick's own view of skirmishing as a dishonorable, detestable and brigand-like business.

The fact that Frederick clung to his Oblique Order (refined from his armchair perspective), and that the Prussians clung to Frederick, meant that they went into the 1806 campaign woefully unprepared for the enemy they met. Scott Bowden describes many of these tactical and organizational differences in his article on the French and Prussian armies of 1806 printed in EE&L #1. As Duffy points out, Frederick fought the War of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years War with the army designed and built by his father. The Duke of Brunswick fought and lost in 1806 with the army designed and built by Frederick.

Sources

On the subject of bibliography, Mr. Raiff's list is excellent. I would only add the Luvaas book and Age of Battles, Russell Weigley, 1991. For sieges, and for a look at Frederick's enemies' armies, Mr. Duffy has authored several useful works. These include: The Army of Maria Theresa, 1977, and Russia's Military Way to the West, 1981.

[1] Quoted in Frederick the Great on the Art of War, p. 176, edited and translated by Jay Luvaas, 1966. A highly recommended book which condenses and translates Frederick's own writings on war, which were used to instruct Prussian officers up to 1806. Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents #11

[2] The Military Life of Frederick the Great, p. 310, Christopher Duffy, 1986.

[3] Op cit, p. 193.

[4] Op cit.

[5] Op cit., p. 201

[6] Op cit., p. 314

© Copyright 1995 by The Emperor's Press