One of the sad parts about the hobby has been that many gamers spend so much effort in super detailing their miniatures and then use any old slab of wood, or strip of mangy felt for hills, streams or roads. At conventions or at home games I have seen the most beautifully detailed and mounted figures jumbled about on a hodge-podge terrain of poorly painted styrofoam, cobbled up H.O. buildings, and dime-store trees.

Lately the hobby seems infatuated with those horrid lumpy, little solid-cast buildings which are no better, and in many cases far worse than the H.O. stuff. On the other hand, model railroaders seem to make the most exquisite and beautiful terrain, and since I am also a model railroader it was only a matter of time before I tried to blend the two. The problem however is that though the terrain on model-railroads is beautiful, it is extremely fragile! The lithe-limbed trees, sculpted hills, and ornate filigree-work of super detailed buildings and barns simply will not stand up to the wear-and-tear of wargaming. Actually this is pretty realistic as real life terrain does not stand up too well to the wear and tear of real war. Nevertheless I was determined to find a medium.

THE BASICS

The most important part of the system, and the most expensive, is the hexagonal bases themselves. These are cut from 1/4" plywood, finished on both sides, called Luan. You don't really have to have it finished on both sides, but it gives a good surface for modeling, a surface that does not have to be "smoothed" when modeling things like streams, or where a wood grain would be unsightly.

MAKING THE TEMPLATE

Make sure that the compass divides the circle perfectly! If it doesn't, do it over again, being careful to be as precise as you can. The more time you spend on this the better your finished product will be. I use the 14" hex (radius of 7") because this makes the finished plate small enough to allow many of them to fit on the table top, yet is still large enough for making models of some complexity. Any smaller and you will have trouble not only modeling things, but making them join together smoothly. Any larger and you can make better models, but you can't fit so many on a table top and the variety of your set up will decrease. You could, of course, make it to whatever size you wish. The 7" radii is set up for 25mm, if you use 15mm you should cut it down to 4".

Once you have divided the circle, take a very sharp pencil, carefully connect the marks around the circle to make a hexagon. Place the steel straight-edge exactly on the sides of the hexagon, and using a very sharp utility knife, cut it out. Hold the straight edge firmly so it doesn't slip, and make several small successive cuts till you cut through the board. Be sure to protect the surface of the workspace you are using. USE THE STRAIGHT EDGE! DO NOT TRY TO DO IT BY EYEBALL OR FREEHAND! YOU WILL NEVER GET IT RIGHT. Further, if you try to cut too deep at once, the blade may wander off the mark and you will have a rough and gouged surface.

CUTTING THE PLATES

I used to make the plates using clamps, fences, and a skill saw. I would cut the sheets of plywood into squares, then clamp a stack of them together, trace the hexagon on the top plate, then use a rotary saw with a cutting "fence" to cut the plates five or six at a time. I abandoned this method because it's not really faster than cutting them individually, nor is it more precise. In fact the plates never came out exactly even when I used a rotary arm saw, so now I just do them one at a time. Besides, cutting though three and four inches of wood is very wearing on the saw, and dulls the blade very quickly, and there is a slight bend that makes the bottom plates in the stack uneven.

I now simply trace a hexagon on the plywood, then cut it out with the sabre saw, then trace another hexagon etc. By working slowly and steadily you get plates that are much more accurate and with a lot less waste. If you have been careful in making your template, the sections should fit together from any angle.

By using three pieces of 4x8 plywood you should have more than enough plates to make a significant amount of terrain features. After cutting go over the edges lightly with a belt sander or orbital sander with a fine-grit to remove any splinters or burrs.

BASIC STUFF

That was the hard part. Now we're going to make a few basic "flat terrain" sections to get you involved in some of the techniques.

The first thing you have to decide is the general color scheme of the terrain. Colonial players in India, Arabia, the Sudan, or even most of the Ancient world outside of Europe will want some shade of yellowish dun, like sand or arid soil. Players of most of the American wars, Europe and Eurasia will have a green forested-farmland landscape. Truly weird persons who like fighting winter campaigns, will want a landscape like Antarctica. People into science fiction can have any color they want.

At the hardware store pick up samples of all the greens, browns, yellows, beige and blues from those custom color-matching stands. Take the samples and open up some old National Geographic magazines that show faraway exotic places and begin matching colors. The best way, however, to do this is to study nature itself, especially if you are living in an area with terrain similar to that you want to model. Take the samples and go out on a sunny day and check the swatches against nature. Do not however try to match the color against grass, ground, or rock close up, but from a distance, for remember your eye on the table top will be viewing the terrain from a "distance". Make the best balance between them.

You are looking for eight basic colors. These are a dark earth tone, and light earth tone, dark vegetation tone (like the color in the inner parts of leafy trees or evergreens), medium vegetation tone (like wet grass or the outer leaves of trees), top vegetation tone (like dry grass, or yellow-green vegetation), and finally a deep water blue, a white, and a rock gray. Notice that nature is never monochrome. No matter how uniform the ground color when you hold a piece of it in your hand, when viewed from a distance the irregularity and subtle "roughness" of the ground causes you to see the same hue at different angles and hence at different reflections. Chose which will be the dominant colors (usually the light earth and medium vegetation and get a gallon of that, and quarts or pints if you can get it, of the other tones. Now this is a lot of paint but you'll only have to buy it once in your life probably. MAKE SURE TO GET ONLY FLAT PAINT!

Now the first thing we're going to make is simple flat open terrain. You can do this by two methods, a simple one, and a more complicated one. I'll describe the latter first. Take the celluclay and mix it with water according to the directions on the bag. One pound will do a LOT, so for flat sections you may want to mix only a quarter or a half the pack at a time. Once it is mixed (and make it a little looser than the instructions call for). Take about a heaping tablespoon or two full of the stuff and slop it onto a plate. Smear it around until it leaves little "nits" all over the plate.

Don't trouble yourself to make its application uniform, nor do you have to cover the entire plate. All you are doing is making a suggestion of "roughness" to the ground. If you want to make a small hummock, simply smooth a bigger dollop down. This stuff is pretty adhesive on its own with the wood grain, but if you are not sure about it, add a little Elmer's Glue to the water. Don't try to make hills or complicated terrain forms yet, this stuff is too expensive and it won't come out right anyway, Don't layer it down more than 1/4" thick at the deepest. By making the stuff a little wetter than called for you will be able to make it quite smooth. If you use less water it will be rougher and more grainy.

Experiment!

Experiment with the textures. All you want to do is make a few textures to the flat plate. Make a few bumps here and there, but keep the stuff smooth and lay it on VERY THIN. Once this dries (about a day) you can paint it. To paint it, take your Dark earth color and paint the low-lying areas of the ground, the small depressions, and the swales between hummocks. You can even make small ovals or irregular meanderings to represent irregular areas of bare wet earth. Let this dry. Then dry-brush around these dark earth areas with the light earth shade to "feather" the edges. Once you get more expert you can work with the darker paint still "tacky" and get a nice blending. Now cover the rest of the area with the medium vegetation, including any small lumps or hummocks you have made. When almost finished, dry-brush a little light vegetation on the tops of the knolls or hummocks and to give it a textured effect.

If you want you can now apply some of the textured "grits" for small stones or gravel or grasses, as sold by the model-railroad shops. I would avoid using the beautiful grass they offer because it's too expensive, and will be wrecked after a few games anyway. Remember, you're going to be putting heavy stands of troops on this stuff and rolling dice over it. I don't like the "sawdust" type grass because it's too green and too shiny, and even the flat stuff looks like astro-turf.

To texture the piece, water down some of the Elmer's Glue by about 30%. "Paint" this all over the surface with a paint-brush, but don't worry if not every inch is covered. The whole surface does not have to be wet. Place the plate in the bottom of a cardboard box and dump the texturing "stuff" over it. After a second or two, pick up the plate and rap it a few times from behind to knock off the stuff that hasn't set in the glue. The plate is now done. You have a textured "plain" terrain section.

The "simple" method mentioned above skips the "celluclay" roughening, using just the paint and "fuzz".

Next time, "more lumpy" and interesting plain terrain sections and some tips about the wide open spaces.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. To accomplish this I created small hexagonal modules which could be as plain or detailed as I wanted, and which could be used interchangeably to assemble a huge variety of table tops. The Hexagons were made by cutting 1/4" plywood and using them as a base for the detailing. I have used this terrain at several conventions to demonstrate games, as well as at our club meetings. Not only is it tremendously strong and durable, easily taking the most callous abuse of unfeeling gamers, I use the hexagons of this system as the basis for movement and fire in my rules. One important part about the hexagonal terrain system is that it's cheap - I use almost exclusively (aside from the paints and adhesives), scrap materials and stuff that can be gathered in any field or alley.

To accomplish this I created small hexagonal modules which could be as plain or detailed as I wanted, and which could be used interchangeably to assemble a huge variety of table tops. The Hexagons were made by cutting 1/4" plywood and using them as a base for the detailing. I have used this terrain at several conventions to demonstrate games, as well as at our club meetings. Not only is it tremendously strong and durable, easily taking the most callous abuse of unfeeling gamers, I use the hexagons of this system as the basis for movement and fire in my rules. One important part about the hexagonal terrain system is that it's cheap - I use almost exclusively (aside from the paints and adhesives), scrap materials and stuff that can be gathered in any field or alley.

Materials needed:

1 Piece of Bristol Board (available at any art supply store) at least 15" x 18" and 1/16 to 1/8" thick

1 Utility knife

1 Compass

1 pencil

1 Carpenters square or any thick, heavy, straight edge

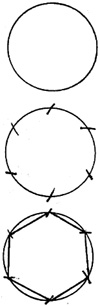

The template is the master cutting diagram. Carefully prepare a clean work surface. Relax, cause this is going take time. Take the bristol board and draw on it a perfect hexagon. To do this use the compass to draw a circle whose diameter defines the size of the hexagon you want (I use a 14" hexagon). Then divide the circle into six segments by using the compass, still set at the radius of the circle you just drew to mark off the divisions. See illustration.

The template is the master cutting diagram. Carefully prepare a clean work surface. Relax, cause this is going take time. Take the bristol board and draw on it a perfect hexagon. To do this use the compass to draw a circle whose diameter defines the size of the hexagon you want (I use a 14" hexagon). Then divide the circle into six segments by using the compass, still set at the radius of the circle you just drew to mark off the divisions. See illustration.

Materials needed:

1-3 Sheets of 4' x 8' x 1/4" Luan plywood, finished bothsides.

1 jig saw or saber saw, with a metal-cutting blade.

Materials needed:

Several Hexagon Plates

Basic ground and vegetation material (see sidebar on how to make your own).

Basic ground and vegetation colors in Latex paint

1 lb of Celluclay, or Celluclay II (available at any artist supply house).

1 2" wide paintbrush

1 1" or 1/2" wide paintbrush.

1 Quart of Elmer's glue or White Glue.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #70

© Copyright 1996 by The Courier Publishing Company.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com