Before the Civil War erupted in 1861 a large amount of seaborne trade passed through

the North Carolina's coastal ports-primarily at Wilmington, but also cities such as New Bern, Washington, Plymouth, Edenton and Elizabeth City. Access to Norfolk and the whole Cheasapeake Bay basin-most of the Mid-Atlantic region- was available through the Albemarle and Chesapeake canal. The sounds provided strategic avenues for the flow of supplies, messages and troop

movements between these-and other-cities.

Before the Civil War erupted in 1861 a large amount of seaborne trade passed through

the North Carolina's coastal ports-primarily at Wilmington, but also cities such as New Bern, Washington, Plymouth, Edenton and Elizabeth City. Access to Norfolk and the whole Cheasapeake Bay basin-most of the Mid-Atlantic region- was available through the Albemarle and Chesapeake canal. The sounds provided strategic avenues for the flow of supplies, messages and troop

movements between these-and other-cities.

At first, the establishment of the Union blockade in April, 1861 seemed a hollow threat to Southern merchants and leaders alike. Federal coastal forts were seized by various groups loyal to the Southern cause, though in most cases these forts were in a state of neglect that the Confederacy could afford little to correct. Further, the Union navy had only three commissioned warships available in domestic ports for use in the blockade. Foreign goods and passengers flowed almost unhindered through the weak coils of the anaconda.

The Blockade Tightens

However, the blockade soon became a force to be reckoned with. In December the Union Navy had over 170 vessels available for the blockade with 52 more vessels nearing completing in shipyards along the East Coast. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was tightening the noose around the neck of the Confederacy's coastal commerce. While the blockade tightened, the Confederates improved their coastal defenses. Forts were improved, guns added, garrisons enlarged (as best they could be). Still, these defenses were seriously under strength, especially in regard to artillery and ammunition.

With frigates interdicting the seaward approaches to the major inlets to the sounds, An army operation under General Ben Butler captured the weak Confederate fortifications at Hatteras Inlet. After the capture of Hatteras Inlet the main Confederate line of resistance lay in the "Mosquito Fleet"-a group of converted small merchants, tugboats, and fishing vessels. Most of these vessels were small, mounting only 1 light gun. While they could never stand up to the Union gunboats, they were effective at harassing Union troops, and raiding the coastal supply lines.

Unfortunately for the Confederacy, theses vessels as well as the "improved" fortifications were swept from the sounds by the amphibious campaign of General Ambrose Burnside's Coastal Division. In a demonstration of the mobility the sounds provided Burnside's troops captured Roanoke Island, Elizabeth City, and New Bern with a rapidity made possible only by absolute control of the sounds. Coastal traffic on North Carolina's sounds fell off to almost nothing. Further, the Wilmington and Wealdon railroad and the Atlantic and North Carolina railroad intersected at Goldsboro, North Carolina. Both rail lines could be threatened and raided by troops delivered and supplied by ships traveling the sounds of coastal North Carolina and up the Neuse river.

Rise of the Ironclad

For the Confederacy, the ironclad warship held the South's salvation for breaking the coastal blockade. The initial success of the ironclad CSS Virginia (converted from the salvaged hull and engines of the Union Navy's steam frigate USS Merrimack) led the Confederate States Navy to embark on a program of ironclad construction. In his definitive work on the Confederate armorclad program Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Ironclads, Dr. William N. Still, Jr. states that in 1862 no fewer than 18 ironclads were laid down across the South.

In North Carolina the ironclad program was dispersed at three sites Wilmington (CSS North Carolina and Raleigh) Kinston (CSS Neuse) and Edwards Ferry (CSS Albemarle). With the exception of Wilmington, the "shipyards" were very primitive, with little or no facilities. The yard at Edward's Ferry for example, started as nothing more than a cornfield, with no sheds, shops or building ways.

The Albemarle was similar to most other Confederate iron-clads. She was small compared to Union ironclads, measuring 152 feet overall length by 34 feet wide and possessing a 9 foot draft. The dominant feature was the octagonal armored citadel enclosing the gun deck. The 6" armor was able to resist shell and shot from all but the largest guns. The Albemarle's main weapon lay in an eighteen foot iron plated ram. Her battery, a pair of 8" Brookes rifles could inflict massive damage on any non-armored warship. The Albemarle's main drawbacks were her low speed of only 4 knots -- making her sluggish and slow to maneuver -- and her nine foot draft would be a operational liability on the shallow waters and shoals of the North Carolina sounds.

In late March, the ship was moved to Hamilton, North Carolina. where the finishing touches were applied. On April 17th, 1864 the Albemarle was hurriedly commissioned to assist the Confederate army's upcoming offensive against Plymouth, in eastern North Carolina. That same day the Albemarle set sail downstream towing a blacksmith's forge and swarming with workmen.

Like most Confederate ironclads the Albemarle suffered from unreliable machinery and material. Almost immediately, her engines failed and rudder control was lost halting her voyage. This delay jeopardized the planned offensive that was then getting underway, and which relied on the Albemarle for a rapid victory. It took ten hours to effect repairs and resume the voyage toward Plymouth.

The Battle of Plymouth, North Carolina

Union control and supply of the upper Albemarle sound and Northeast North Carolina. Plymouth is located next to the Roanoke river, on an open, coastal plain. Though the terrain is open the ground is swampy and broken. First settled in 1720 Plymouths strategic location boosted its growth and stimulated trade. The town was named a "port of Delivery" in 1790 and a "Port of Entry" in 1808. By 1848 it was not unusual to find more than fifty boats docked along the river front. However, 1848 also held catastrophe for Plymouth when yellow fever decimated the population, leaving three hundred survivors.

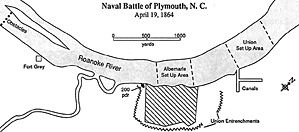

Larger version of Plymouth Map (slow: 41K)

Larger version of Plymouth Map (slow: 41K)

In early April, 1864 Plymouth was held by 3,000 troops defending a system of river batteries and earthworks that encircled the entire city. Upstream from the city the Union forces had blockaded the Roanoke river to keep the Albemarle bottled up. In addition, there was a small squadron of Union gunboats-USS Miami, USS Ceres, USS Southfield, and the armed transport USS Bombshell, aiding in the defense of the city. The Union squadron was commanded by Commander Charles Flusser.

To capture Plymouth, the Confederacy had allocated three brigades of troops under Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke. Hoke's plan envisioned Plymouth as the first domino to fall in the liberation of eastern North Carolina from Union control. Following this success, the Albemarle would be free to sweep the Union navy from the Albemarle, Roanoke and Pamlico sounds-possibly linking up with the ironclad Neuse, then being completed at Kinston.

Early Morn, April 18th, 1864

The battle for Plymouth began in the early morning light of April 18th, 1864. General Hoke's troops laid siege to Plymouth, concentrating their fire on the outlying positions and the Union ships in the river. A shot from a strategically placed 32 par damaged the USS Bombshell sufficiently that she retreated and later sank at her moorings in Plymouth. The gunboat Ceres was heavily damaged, suffering nine men killed and wounded out of a crew of 45. Commander Flusser pulled the Union gunboats back downstream and waited for the ironclad to arrive.

Flusser's plan was to trap the ironclad in hawser cables strung between his two undamaged gunboats-the Miami and the Southfield. Then after fouling the ironclad-eliminating the threat of ramming-he could destroy the Albemarle with the massed close range firepower of his heavy guns. William N. Trotter in Ironclads and Columbiads: The Civil War in North Carolina, illustrates that Flusser was not afflicted by "ram fever" . Trotter quotes Flusser's conversation with some local wives that "...we shall sink, destroy, or capture it (the Albemarle), or find our graves in the Roanoke."

The Albemarle did not near the battlefield until late in the day. A reconnaissance by Gilbert Elliot-who managed the construction of the Albemarle-found that the rivers current had carved a gap through the Union's underwater obstacles wide enough for the Albemarle to pass, allowing the ironclad to descend upon the city.

At three o'clock in the morning the Albemarle began steaming the convoluted path through the obstacles toward Plymouth. Clearing the obstacles near dawn, the Albemarle was engaged by the guns of Fort Grey-a 100 pounder and two 32 pounders-located west of Plymouth on the south bank of the Roanoke. The fire-even the 100 pounder- had no effect on the Albemarle and she was quickly past them. Steaming past Plymouth she encountered the Union gunboats USS Miami and USS Southfield covering the USS Whitehead and the damaged gunboat Ceres.

At three o'clock in the morning the Albemarle began steaming the convoluted path through the obstacles toward Plymouth. Clearing the obstacles near dawn, the Albemarle was engaged by the guns of Fort Grey-a 100 pounder and two 32 pounders-located west of Plymouth on the south bank of the Roanoke. The fire-even the 100 pounder- had no effect on the Albemarle and she was quickly past them. Steaming past Plymouth she encountered the Union gunboats USS Miami and USS Southfield covering the USS Whitehead and the damaged gunboat Ceres.

As the Albemarle neared the Union ships Commander Cooke deduced the Union intention to foul his ship. He ordered the Albemarle to hug the river bank and then swung the wheel over and aimed for the Southfield. The Albemarle struck home, tearing a gaping hole in the Southfield dear through to the boilers. The Southfield immediately began to sink-taking the Albemarle with her. Forturnately for the Confederates the South-field hit the shallow bottom and rolled over, freeing the Albe-marle from her deadly embrace.

Meanwhile, Commander Flusser in the Miami had closed and grappled with the temporarily immobilized Albemarle. With the vessels locked together the Miami's crew launched a boarding party against the Albemarle. Commander Cooke had thought of this possibility and stationed about twenty-four men topside on the superstructure. These men poured rifle and pistol fire against any exposed member of the Miami's crew. The boarding attempt failed.

Now occurred one of those bizarre instances that fate dictates and wargames poorly recreate. Onboard the Miami, Commander Flusser personally directed his heaviest gun-a 100 pound Parrot rifle loaded with a high explosive shell-against the Albemarle. At point blank range Flusser fired the gun himself-the shot struck the armored plate of the Albemarle, ricocheted in a shower of sparks and landed back on the Miami's deck a few feet from where Flusser stood. Commander Flusser stood shocked as the shell detonated, killing 10 men and most of the officers-including Commander Charles Flusser.

Adding to the carnage, Cooke ordered the Albemarle's 8 inch Brookes rifles fired into the Miami. At point blank range it was impossible to miss the wooden hulled gunboat. Lieutenant Charles A. French, commander of the sunken Southfield and now temporarily in command of the damaged Miami withdrew the Miami and ordered the rest of the squadron disengaged down the Roanoke River.

On to Plymouth

Plymouth lay open to the guns of the Albemarle. Commander Cooke spent the rest of the day and into the night bombarding the city. General Hoke also maintained his barrage of Plymouth and repositioned his troops for an attack. The next day, April 20th, 1864, Plymouth fell to the Confederate troops. The ironclad had certainly played a key role in the victory first in eliminating the Union's supporting gunboat squadron (easily worth several batteries of artillery for General Wessells and the Union defend-ers) and then in support of Hoke's assault on the 20th, where the ship provided deadly enfilading fire.

Following the fall of Plymouth, General Hoke pursued his plans for victory in coastal North Carolina. On April 27th, General Hoke laid siege to Washington, North Carolina. Three days later, the city fell opening the road to New Bern-Hoke's next major objective. Also on the 27th, the ironclad CSS Neuse, a near sister to the Albemarle was completed at Kinston, North Carolina. General Hoke planned on using the Neuse for support exactly as he used the Albemarle at Plymouth. Unfortunately for General Hoke, and the Confederacy, the Neuse ran aground on her first voyage effectively ending her career.

General Hoke, having lost his naval support on the Nuese River, prevailed upon Commander Cooke and the Albemarle to assist in the attack on New Bern. This was a tall order for the Confederate ironclad, which had difficulty steaming the twenty miles downstream from Hamilton to Plymouth. For this battle Cooke's vessel would have to sail down the Roanoke, cross the Albemarle, Croatan and Pamlico sounds, then steam up the obstructed and heavily defended Neuse river to New Bern.

Further, the Union Navy's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was massing a squadron of gunboats, under Captain Melancton Smith (USN) at the mouth of the Roanoke river to contain the Albemarle. Commander Cooke could be thankful that the Union squadron contained no monitors or other ironclads, but he still faced a powerful force. Captain Smith had a core force of four double ender gunboats: the repaired Miami and the Sassacus, Mattabesett and the Wyalusing, and three smaller gunboats the converted ferryboats USS Commodore Hull, Issac N. Seymour and another veteran of the Plymouth battle the gunboat USS Whitehead.

In support of this operation Commander Cooke could rely on the aid of two Confederate vessels the Cotton Plant and the resurrected ex-Union Bombshell. These two craft hardly qualified as combatants-the Cotton plant carried only small arms while the Bombshell had but a single gun. These ships appear more than likely to have been auxiliary vessels to support the Albemarle on her open water cruise -- providing work crews and a tow in case of emergency -- than as warships expected to engage the enemy.

Captain Smith planned on using his overwhelming numbers to isolate the Albemarle and keep her under continuos fire from the heavy 100 pound Parrotts and nine inch Dalghren smooth-bore guns. The Miami had been equipped with a spar torpedo on a long boom. Smith hoped to place this explosive charge under the Albemarle's keel and rip open her bottom. Smith's double-enders also had nets that could be used to foul the Albemarle's propellers if the occasion arose.

THE BATTLE OF ALBEMARLE SOUND, MAY 5th, 1864

At 5:00 pm battle was joined. The Albemarle preceded her two escorts while the Union force was formed into two groups- the double enders in line ahead while the other vessels in reserve. The Albemarle drew first blood, scoring a hit on the Mattabesett. She then traded shots with the Sassacus.

The Sassacus' captain Commander Roe watched in horror as his 100pdr shells split apart against the Ablemarle's hull, or ricocheted off the armor causing no damage. The two ships then passed out of range and the Sassacus forced the salvaged Bombshell to strike her colors. This left only the Albemarle to face the Union ships as the Cotton Plant had already withdrawn.

Commander Roe, seized the initiative and rammed the Albemarle on the starboard side near the point were the casemate joined the hull. The force of the impact knocked most of the Albemarle's crew to the ground and rolled the vessel enough to take on several tons of water. The two vessels became locked together. Unfortunately for the Sassacus the Albemarle fired her 8" rifle into the hull of the stationary Sassacus, shattering her boiler and filling the ship with scalding steam.

Though the Union now possessed a superiority of firepower no other Union ship closed with the Albemarle. The ships traded shot with the Union taking the worst of the damage. However, the Albemarle was not untouched. Her armor plate was cracked in several places. Her smokestack resembled Swiss cheese reducing her speed to almost nothing and filling the ship with smoke. Also, the steering gear was heavily damaged making the ship almost unmaneuverable. Commander Cooke ordered the ship back to Plymouth, to repair the damage.

THE VERDICT OF HISTORY

Historically, the Albemarle's campaign did little to influence the outcome of war. Her triumphant victory over the Southfield and Miami at Plymouth was overshadowed by her failure on the 5th of May and her later destruction by a Union raiding party. General Hoke's liberation of east-central North Carolina gained the Confederacy little of real value. Although Plymouth was liberated the loss of the Neuse and failure of the Albemarle to break past the Union gunboats crippled the land operation against New Bern.

The city of Plymouth fared badly from the campaign. A microcosm of the Albemarle region, at the wars end only eleven buildings remained standing in Plymouth. Though the city slowly recovered-mainly from naval stores trade and the lumber industry - it never regained its former glory.

As a result of his success at Plymouth, General Hoke, the architect of the Albemarle's campaign was promoted to Major General and went on to command a division in the Richmond and Petersburg campaigns as well as serving as the field commander for Braxton Bragg in the battles for Fort Fisher. After the war, Robert Hoke faded back into the obscurity of civilian life. He died in Raleigh, North Carolina on July 3rd, 1912.

The Albemarle can be likened as a 19th century version of the World War Two battleship German Tirpitz. Both were designed to be superior to most existing warships, both enjoyed only limited success and both were destroyed as the result of specially formed raiding forces (note the parallel between Lt. Cushing's' steam launch attack against the Albemarle and the Royal Navy's X-craft attacks and the RAF's specialist bomber squadron against the Tirpitz). Today the remains of the Albemarle's sister Neuse is on display in Kinston, North Carolina.

Gaming the Albemarle's Campaign

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #65

© Copyright 1994 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com