When Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford began his invasion of Zululand in January 1879 he did so without access to any modern

signalling equipment. Besides despatch riders and runners, the only other

means available to him was the use of semaphore signalling with hand

held flags. The heliograph, which had been used successfully in

Afghanistan the previous year, was still being introduced in the rest of the

Army and was at that time not available in southern Africa.

The heliograph was an instrument which used a mirror to reflect

sunlight in a series of long and short flashes representing the alphabet

invented by Samuel Morse. The apparatus had been devised by Henry

Mance of the Government Persian Gulf Telegraph Department in 1869

while he was serving in India. In 1873 the Quartermaster-General

reported to the Commanderin-Chief in India that trials had proved

successful, resulting in the introduction of the heliograph to troops in

India.

After his disasterous reverse at Isandlwana early in the campaign

Chelmsford was forced to withdraw the remains of the Centre Column

back into Natal while he awaited reinforcements despatched by the

home government. However, Chelmsford's invasion had been formed of

three separate columns and now the Coastal Column, under Colonel

C.K. Pearson, was isolated at the deserted mission station at Eshowe.

Shortly after news reached him of Chelmsford's reversal of fortune

Pearson found himself loosely invested by the Zulus but unable to

extricate himself safely from his position. Determined to hold his ground

Pearson completed the defences he had begun to dig around the mission

and sat back to await relief.

Eshowe was situated on high ground about 35 miles by rough track

from the Zululand/Natal border on the Thukela river. However by line of

sight it was only about 25 miles from Fort Pearson, the British camp on

the Natal bank of the Thukela. If heliographs had been available then this

was an ideal situation for their use as, according to the Indian report, the

signals they produced were "perfectly clear, and could easily be read, in

ordinary weather, at a distance of fifty miles, without a telescope."

Eshowe Communications

Pearson had occupied Eshowe on 23 January and had managed to

keep up erratic communications with Fort Pearson by means of black

runners but after 11 February no further messages were received. The

Zulus had tightened the cordon, now Pearson's force was cut off and

alone.

Back at Fort Pearson the inability to communicate with Eshowe was

causing concern. Following an unsuccessful attempt to make contact using

rockets, communication was restored on 2 March using the simplest of all

forms of 'heliograph'. Lieutenant C. E. Haynes of 2nd Company, Royal

Engineers, had taken possession of a bedroom mirror from one of the

rooms of Smith's Hotel, situated close to Fort Pearson and had begun to

flash signals in the direction of Eshowe. The excitement at Eshowe was

great but it took another four days before the full message was

understood.

Determined to return the signal, Pearson's engineers began work

devising somewhat eccentric means of reopening communications. These

included a hot-air halloon made from tracing paper and a large pivoting

screen of black tarpaulin. Both attempts failed due to bad weather. But

success was close at hand. When Pearson had first realised his

predicament at Eshowe he had sent his mounted men back to Natal to help

preserve his food supplies. These men had been obliged to leave their

baggage behind, and now a search revealed a mirror 18 inches by 12

inches.

Mirror, Mirror

The mirror was handed to Captain H.G. Macgregor of the 29th

Regiment who was serving on Pearson's staff. Macgregor's first attempt

was a failure. Having found a piece of old pipe in the church at Eshowe he

laid it on two sacks and aimed it in the direction of Fort Pearson. He then

angled the mirror on top of a large box and reflected the sunlight down a

pipe. Unfortunately to determine whether the light was travelling down the

length of the pipe his assistant had to look down the end until the sun

dazzled him. Once the light travelled the length of the pipe the light beam

could be interrupted by a board attached to the operator's hand. To save

the assistant's eyesight it was suggested that by covering the ends of the

pipe with paper the sunlight would illuminate them when it was correctly

aligned. But with the movement of the sun, which was behind the signallers for most of the day, the whole apparatus had to be realigned every few minutes. Not surprisingly, no signal was ever received at Fort Pearson by this method.

A second system however proved much more successful. Captain

G.K.E. Beddoes of the Natal Native Pioneers solved the problem of the

moving sun by fixing the mirror on a pivot so it could easily be realigned.

The pivot was then placed on top of a barrel and a sighting system of wire

directing rods was erected. The Morse flashes were still made by

interrupting the light with a board strapped to the operator's hand, but it worked. On 14

March two way communication was opened and remained in operation until Eshowe was relieved on 3 March.

C Telegraph Troop

With the successful relief of Eshowe, Lord Chelmsford now turned his attention

to plans for a second invasion of Zululand. Throughout March and the early part of

April reinforcements had heen pouring into Natal and marching to their allocated

bases of operation. Almost as an afterthought the Right Half of C Telegraph Troop, Royal Engineers, were embarked on the 'Borussia' and set sail from Portsmouth on 1st April.

Commanded by Major A.C. Hamilton (later the 10th Lord Belhaven and Stenton) the detachment comprised 5 officers, 172 men, 109 horses and 13 wagons and carriages. On arrival in Natal, presumably in early May, Hamilton was made Director of Telegraphs and signalling. Prior to leaving England Hamilton had found it necessary to point out the futility of sending him to

Natal with only his peacetime allowance of cable, about 20 miles.

On arrival in Durban C Troop were issued with four heliographs which had been despatched from the workshops of the Bengal Sappers and Miners

at Roorkee in India. At home C Troop had been using heliostats but

happily found that the heliographs gave a much steadier signal. The

heliostat used a fixed mirror with a shutter to interrupt the beam. The

heliograph had an oscilating mirror which reflected the signal flashes to

the receiving station.

It is very difficult to determine the exact movements of C Troop's

heliographs in Zululand. Part of C Troop were certainly involved in laying

telegraph cables on the line of advance of Major-General H.H.

Crealock's First Division. By 30 May they had completed a telegraph

line which connected Fort Pearson with Forts Crealock and Chelmsford,

the shortage of cable being made good with uninsulated fence wire. The

whole Troop appears to have been broken up into small detachments

and widely distributed. However, an account in the 'Illustrated London

News' for 6 September 1879, during the post Ulundi period, states that the heliographs were positioned at Altezeli (presumably Itelezi, where the British had built Fort Warwick) (Fort)

Marshall, (Fort) Evelyn Wood and Kamagwasa.

Officer Responsibilities

The distribution of the officers of the Troop, given below

demonstrates their responsibilities during the latter stages of the

campaign. As there were four heliographs, perhaps it is possible that

each Lieutenant was responsible for one instrument.

Heliographs did not dramatically change the face of war in southern Africa, but there is no doubt that their introduction provided a relatively simple and easy to transport communication system that could operate effectively in the field. Encouraged by the success it

was reported in the Illustrated London News on 13 September 1879 that a further twelve were being despatched to southern Africa from the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich. Compared with bedroom mirrors and tarpaulin screens it was a great improvement.

Bourquin, S.I., Johnston, T.M., 'The Zulu War of 1879 as Reported in the

Illustrated London News during January-December 1879', Durban, 1971. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Friends at a Distance: An illustration which appeared in the 'Illustrated London News' of 31 May 1879 shows the two Eshowe heliographs. Right-hand panel shows the first effort by the garrison, which failed to contact Fort Pearson. The left-hand panel shows the successful verion using Captain Beddoes' pivoting mirror.

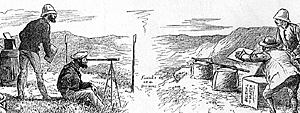

Friends at a Distance: An illustration which appeared in the 'Illustrated London News' of 31 May 1879 shows the two Eshowe heliographs. Right-hand panel shows the first effort by the garrison, which failed to contact Fort Pearson. The left-hand panel shows the successful verion using Captain Beddoes' pivoting mirror.

Signalling to Eshowe by Sun Flashing, 25 March 1879: Sketch by John North Crealock. In thebackground can be seen the bedroom mirror from Smith's Hotel that was used to signal Eshowe. It appears that the beam of light was interrupted by a signal flag to form the Morse alphabet. The system first successfully transmitted on 2 March 1879, althoughit took four days for the full message to be understood by the besieged garrison.

Signalling to Eshowe by Sun Flashing, 25 March 1879: Sketch by John North Crealock. In thebackground can be seen the bedroom mirror from Smith's Hotel that was used to signal Eshowe. It appears that the beam of light was interrupted by a signal flag to form the Morse alphabet. The system first successfully transmitted on 2 March 1879, althoughit took four days for the full message to be understood by the besieged garrison.

Heliograph at Work, Flashing Messages to a Beleagured Force: From the Illustrated London News of 26 April 1879. This very attractive engraving is fictional, as the first heliographs were issued to C Telegraph Troop only in May. Perhaps the artist in London had read the article in the newspaper for 12 April 1879 (communications with Eshowe via sun flashing) and concluded that heliographs were being used.

Heliograph at Work, Flashing Messages to a Beleagured Force: From the Illustrated London News of 26 April 1879. This very attractive engraving is fictional, as the first heliographs were issued to C Telegraph Troop only in May. Perhaps the artist in London had read the article in the newspaper for 12 April 1879 (communications with Eshowe via sun flashing) and concluded that heliographs were being used.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Castle, I. and Knight, I., 'Fearful Hard Times - the siege and relief of Eshowe 1879',

London, 1995.

Knight, I. and Castle, I. 'The Zulu War - Then and Now', London, 1993.

Mackinnon, J.R. and Shadbolt, S.H., 'The South African Campaign 1879', London

1880 (reprinted 1980 and 1995).

War Office, Intelligence Branch (Rothwell, J.S. comp.) 'Narrative of Field Operations

Connected With the Zulu War of 1879', London, 1881 (reprinted 1906 and 1989).

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 11 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com