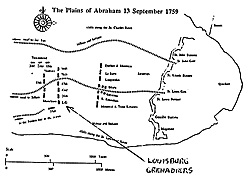

For many of us the battle on the Plains of Abraham, with General Wolfe leading the 28th Foot and Louisburg Grenadiers on the right flank and his subsequent death. is one of the most familiar and famous "moments" of the French and Indian War in North America. However, at least one particular officer has fallen hy the wayside of history. It doesn't help that he shares the surname of one of the Quebec Brigadiers.

I first came across Lt. Colonel Alexander Murray in October 1992, in thc bibliography of Alan J. Guys' Economy and Discipline. The years quoted in the entry under his name covered our period, but who was he and where had he served? I was not long in finding out, and what a surprise it turned out to be.

Initially my search had me getting in touch with Major R.A. Creamer of the Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters, my local regiment, and it was the annals of the Foresters (45th Foot) where I was destined to find Murray. I came across a collection of the arrivals in a local library--they had been staring me in the face all along. Thus while most of the country was busy with Christmas that December, I was getting to know the elusive Lt. Colonel, who, it turned out, was the commanding offlcer of that robust little battalion: the Louisburg Grenadiers.

Ensign Murray

His printed letters with the 45th Foot start with Gibraltar in 1742 and run

through Quebec in 1759.[1] His first commission was as Ensign in the 17th Foot on July 24. 1739, followed by Lieutenant in the 6th Foot on January 19,

1740; Captain 45th Foot April 19, 1742; Major 45th Foot October 1, 1755;

Lieutenant Colonel of the Louisburg Grenadiers on December 31, 1758.[2] Of

the many letters which survived, the Quebec campaign is the best known. Let us

see how Lt. Colonel Alexander Murray of the 45th Foot was involved.

With the date of his local commission already mentioned, we get to see

Wolfe pushing for his services to "command a little battalion of

grenadiers."[3] This little battalion was composed of the grenadier

companies of the Louisbourg garrison: the 22nd, 40th, and 45th Foot. Their

original strength is given in a return dated Neptune at Sea, 5th June,

1759 as 13 officers, 13 NCOs and 300 rank and file. [4]

Montmorency Camp

He first appears at the Montmorency camp, where he'd kept "perfect

health", but the French had Indians causing a disturbance in the area and his

grenadiers had sulfered 2 dead of the 22nd, with 2 more wounded and one

man killed of the 45th company. They were soon to be under fire again.

On July 31st, British flat bottomed boats rowed to the Montmorency

beach, for a frontal assault on the Beauport entrenchments. The grenadiers

were landed and they charged with great intrepidity, the company of

the 22nd behaved extremely well and were the first who got into a

redoubt and battery. McLeod, his servent, was killed in the rush, having on his

person several of Murray's belongings. Murray was thought to be wounded in

the head, but this turned out to be blood smeared from his mouth over his face.

He came dangerously close to being hit, receiving four shots thro' my

clothes. I have indeed reason to thank Almighty God, he exclaimed

afterword. That evening he suppered with General Wolfe and recovered in

Brigadier Murray's bed. [5]

The pace slowed a little for Lt. Colonel Murray. He and his grenadiers

were moved to a village called L'Ange Gardien on the 19th of August, about

two miles below the halls of Montmorency. The small battalion appears to

have been covering a hody of Highlanders, Light Infantry and Rangers

operating on the north side of the St. Lawrence River. Murray had his

headquarters in a fine church which we fortified, and, as it is all stone, a very

strong castle. He was lodged up in the vestry and had been ill for a few

days, apparently this illness had heen spreading through the army. He'd gone a

bit thin, although he had not lost any of his appetite.

On the 12th of September with about 3,000 men under Brigadier Murray,

the grenadiers embarked on board their transports, and put into the boats at

about midnight. The Anse au Foulon looked daunting, Murray described the

cliff as the back of the castle at Edinburgh and they got up the best

way we could and formed.

Around 8:00 a.m, on the 13th, the French army advanced in column to try and break our center and moved troops to surround the British left flank. The British advanced slowly and resolutely to receive them. The French fired from a distance which went over us . The distance between the two armies got gradually closer.

Murray describes it at about 20 paces when we begane to platoon,

and then gave a general fire, after that there was no restraining the men.

The Louisburg Grenadiers ran in with the bayonet and the Highlanders joined

them with their swords. Several of my grenadiers' bayonets were

bent, wrote Murray, their muzzles dipped in gore. He was now a

knight of the order of St. Louis, having took a cross and a sword

with his own hands from a French officer of the Guyenne regiment.

As for the Loiusburg Grenadiers, casualties were one Lt., and three men

killed, with one Capt., two Lts, and 47 men wounded. The Lt. was H. Jones of

the 22nd (killed), Captain J. Cosnan, Lt. J. Pinhorne andLt. H. Nevin all of the

45th Foot were the wounded officers. Pinhorne died of his wounds on the 29th

Sept. [6]

With the battle over, the grenadiers joined the rest of the army in

securing a camp, working all through the 14th. With the following capitulation,

Murray wrote: I took possession with the Grenadiers of the Army.

Of the original 13 officers of the Louisburg Grenadiers, 8 were killed or

wounded, and of the 313 other ranks, 125 became casualties.[7] Let Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Murray have the final word: I fancy the Grendaiers and I will be ordered to join their corps. They are fine fellows, and I believe they would lay down their lives for me.[8]

Footnotes

[1] Unfortunately for us, his subsequent career in the 55th and 48th Regiments after Quebec are beyond the scope of the arrivals; they would make

fascinating reading if they have been published. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Larger version of map at right: warning: big file--slow download.

Larger version of map at right: warning: big file--slow download.

[2] Details from the Regiments Arrival, edited hy Colonel HC Wylly in 1926; a picture of Murray as a youth is reproduced in the 1925 volume.

[3] Letter from Wolfe to Murray, London 28th January 1759. They were probably acquainted during the siege of Louisburg. After Wolfe's death, Murray certainly missed him: I have nobody now to represent my services (which I am sure has been this campaign with all my soul) since I lost my good friend Wolfe, who would have set my actions off in true light, had he lived. Letter from Murray to his Wife, Quebec September 28, 1759.

[4] Wylly - History of the Sherwood Foresters, Vol I, pg. 46.

[5] It appears that Murray was a favorite of the army, going by the nickname of "the old soldier," though it probably referred to the time he had served in

America, more so than to his age.

[6] Wylly - page 46 and Murray's own account.

[7] Wylly - page 46.

[8] Murray to his wife on the 20th September, 1759. They were gone from the Quebec garrison at the latest on the 29th October according to Wylly. Murray

was to see further action on February 25, 1760 when he was Colonel of the 55th Foot. He was to transfer to the 48th Foot on March 20, 1760, but was destined not to survive the war, dying (from illness?) in the Martinique campaign on the 19th March, 1762.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. IX No. 2 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1996 by James E. Purky

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com