Admiral Lord Cochrane, as he was finally to become, was one of Britain's greatest ever naval heroes, ranking with Nelson and Pellew for seamanship and tactical ability. Perhaps even outshining them with his flamboyant style, self belief, and consistent triumph against the most daunting odds.

In 1814, after a spectacular career in the Royal Navy as a frigate captain, Cochrane was implicated in the great stock exchange fraud of that year, together with the central figure in that affair, his uncle, Andrew Cochrane-Johnstone. The irregularities of the trial, presided over by the invidious Lord Chief Justice Ellenborough, were many, but the verdict was never in any doubt. A selfless and completely honourable man, he was almost certainly innocent, but was convicted and sentenced to a term of one years' imprisonment in the King's Bench prison, together with a fine of £1000. He was discharged from the Royal Navy and struck from the Order of the Knights of the Bath.

At last, his enemies had him a) their mercy, and they treated him with a vengeful and unabated malice. for in addition to his fine and imprisonment, he was to be put in the pillory (stocks), to suffer the ridicule and mockery of the public. There were many who thought it deplorable that one of Britain's great heroes should suffer such a humiliating and degrading sentence. When questioned, Cochrane merely replied "If I am guilty, I richly merit the whole of the sentence passed upon me. If innocent, one penalty cannot be inflicted with more justice than another".

Thankfully the sentence of the pillory was revoked. Cochrane still had many who believed in his innocence, and at a meeting of his constituents, he was unanimously voted as a man still worthy to represent them. His eighteen year old wife Kitty loyally stood by him and Cochrane resolutely proclaimed his honesty

After a year, his term of imprisonment expired, and he could be released on payment of his fine. He at first refused to pay, but later yielded his bank note with the following inscription upon it.

My health having suffered by long and close confinement, and my oppressors being resolved to deprive me of property or life, I submit to robbery to protect myself from murder, in the hope that 'I shall live to bring the delinquents to justice '

On his release, Cochrane worked on his designs for gas warfare, or 'stink vessels' as he called them, together with various other inventions. Some, including Cochrane, may have thought that his days as a naval commander were over after his discharge from the Royal Navy Little did he know at the time, that there was a large proportion of the legend still to be written, and many battles still to be fought.

To Chile

In mid 1818, Cochrane was approached by Don Jose Alvarez, representative of the infant Chilean Republic in South America. He offered Cochrane total command of the Chilean Navy in their fight for independence against Spain. Cochrane accepted, turning down the offer of an Admirals post in the Spanish Navy, and in August of 1818 he set sail for Chile with his rife Kitty, who by now had given him two sons, Thomas, aged four, and William, five months.

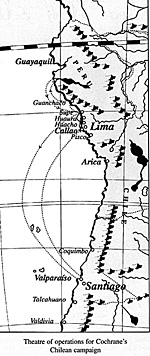

Chile had been fighting the Spanish for their freedom since 1794, but their main problem was that with the long coastline of the country, and the Spanish Navy controlling the seas, victory ass virtually impossible to achieve. The Spaniards had two strong naval bases, Calloa in the north, in Peru, and Valdivia in the south in Chile. Spain kept these bases well supplied from the sea, and struck out at the Chilean Rebels from there. The Spaniards knew Cochrane well from his exploits against them in the wars of 1801 - 1808, and named him simply 'Il Diablo'.

Cochrane was to work with the Chilean leaders General Bernado O'Higgins and Jose de San Martin, but the plan Cochrane had in mind was on a grand scale, and involved not just the liberation of Chile, but the whole of South America. His plan ass, that when the moment as right, he would rescue the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte from exile on the island of St. Helena, and endeavour to place him at the head of a great new South American republic. Who knows what history would have been written if he had succeeded.

On the 28th of November 1818 Cochrane landed at the Chilean base of Valparaiso, there he was well received both the Chileans and the large British contingent there.

This was the beginning of his adventures as a mercenary Admiral, and although in the future he would help both the Brazilians and the Greeks achieve their independence, it was in the service of Chile that his most notable victories came, and where he was perhaps happiest. He also found that the Chileans as a whole were easy to turn into competent sailors, whereas he often despaired of the Brazilians and the Greeks.

He reviewed the Chilean Navy that lay at anchor at Valparaiso, and saw for the first time his new flagship the 'O'Higgins', of 50 guns. His other ships included the 'San Martin', and the 'Lautaro', of 56 and 44 guns respectively, and four other vessels mounting between 14 and 20 guns each. With this force, Cochrane would have to contest for the mastery of the seas with a Spanish Navy that included 14 ships and 28 gunboats. The most powerful ship in the Spanish Navy was the frigate 'Esmeralda', which mounted 44 guns and was easily a match for anything in the Chilean fleet.

Offensive

Upon taking control, Cochrane typically rent straight on the offensive, sailing with his four largest ships north to the coast of Peru to assault the Spanish naval base at Callao. Cochrane was forced to abandon his original plan after it was ruined by foul weather, and the rigging of the 'O'Higgins' being cut up by the shore batteries. He contented himself with blockading the port, raiding Spanish bases along the coast, and plundering their ships at sea. He captured 70000 dollars from the port of Patavilca, and a further 6000 after running down the Spanish brig 'Gazelle'.

After refitting his ships at Valparaiso, Cochrane turned his attentions to the Spanish base in the south of Chile, Valdina. In early 1820 he arrived at his destination, but only after an alarming incident there the 'O'Higgins' was holed on a reef, and only saved from sinking by Cochrane's skill as a carpenter.

At first Cochrane tried trickery, masquerading as a Spanish force to gain entry to the stronghold, but his ruse was discovered and the defenders opened fire. Cochrane gave the order to attack, and the mercenary Major Miller attempted to force a landing with 44 Chilean Marines, hampered by the fact that the badly leaking 'O'Higgins' was lagging behind and unable to give support. However, Miller pushed home the attack regardless, driving the more numerous Spaniards from the beach and establishing a much needed landing point for the Chilean force. Miller's success in this action becomes all the more incredible when one takes into account that the Chilean Marines had virtually no ammunition, as their gunpowder was still soaked in sea-water aboard the 'O'Higgins', and they had carried the day with their bayonets alone!

Cochrane now landed his entire assault force, consisting of only 250 men, this figure including Miller's marines. The enormity of what he was attempting becomes clearer with a brief overview of the defences Valdivia itself is a natural harbour at the mouth of the Valdivia river, it is surrounded by three sides by land with a narrow entrance, only 1200 yards across, to the north. Protecting the harbour were four wooden forts. Three on the western side, Fort lngles, Fort San Carlos, and Fort Amargos; and one on the Eastern aide, Fort Niebla. Also on the western side was the stone built Corral Castle. All but one of these could bring their guns to bear on the harbour entrance, a formidable proposition indeed.

As ever, Cochrane conducted his operation with brilliant tactical ability, and more than a hint of an Errol Flynn script. After nightfall, Cochrane began his attack by sending half his men marching towards Fort Ingles, shouting and firing their weapons into the air as they went.

As the Spanish concentrated their attention on this force, the other half of Cochrane's men had silently made their way to the rear of the fort, scaled the rails and gained entry unnoticed. This done, they poured down volley after volley of withering fire on the defenders. In the dark and confusion Spanish morale broke down and the rout began.

The Spanish abandoned Fort Ingles and fled to their nearest safe position, Fort San Carlos. The garrison here opened the gates to admit their comrades, and this was to prove their undoing. 80 close were the Chileans behind the Spaniards that the gates could not be closed in time to keep them out, and the rout continued into Fort San Carlos. Almost unbelievably, this situation was repeated at Fort Amargos, the last fort on the western side, leaving only the Corral Castle in Spanish hands. Whilst still in possession of the castle, the Spanish were still theoretically in a strong position, but when the 'O'Higgins' at last sailed into view, they assumed that it was bringing fresh reinforcements, and simply abandoned their positions, running inland with whatever they could carry.

Spain's great military base in Chile had been taken at the cost of a mere 26 casualties. In this case, as in the rest of his career, Cochrane had gained a great victory at minimal cost to his men. Left behind by the Spaniards were 50 tons of gunpowder, 10 300 cannon shot, 170,000 musket cartridges, over 1000 muskets, 128 pieces of artillery, and 20 000 dollars.

Cochrane returned home to the Valparaiso and accepted the inevitable hero's welcome and the congratulations of the government. What soured his victory was the predictable argument over prize money. Cochrane strengthened his hand in this situation by refusing to hand over what he had taken, and at one point even tendered his resignation in protest. This was later withdrawn after personal pleas from O'Higgins and San Carlos convinced him to change his mind.

Off the Coast of Peru

Cochrane's next operation was to be against the Spanish base in the north, Call, on the coast of Peru. It was to be a joint operation between the navy, under Cochrane, and the Chilean land forces, under San Martin. San Martin infuriated Cochrane with his lack of zeal and flat refusal to take any offensive action. After a reconnaissance of Calloa itself, made in the now repaired 'O'Higgins', Cochrane found the frigate 'Esmeralda' at anchor there, as well as both British and American warships. Far from wanting to destroy the ship, Cochrane thought that It would make a wonderful addition to the Chilean Navy, if he could capture it. The cutting out of the 'Esmeralda' would be one his most famous and daring exploits.

Cochrane, leading from the front, took his men into the harbour in the dead of night in a number of small bests. Each of his men rare issued with a pistol and a cutlass For use in the close hand to hand fighting in which they were all about to be involved. This was vintage Cochrane, His men, as yet unnoticed, climbed silently up the sides of the 'Esmeralda', and then suddenly all exploded into life as Cochrane leapt over the rail and shouted "Up my lads! She's ours!". The decks of the ship soon became a bloody melee as the Chileans poured over onto the 'Esmeralda' and the Spanish crew responded to the alarm. It ass a hard fought battle, the issue for some time in doubt, and Cochrane was shot through the thigh by a musket ball. Undaunted he struggled on, for such a man will not be denied while he lives. Eventually, the Chileans overpowered the defenders and gained control of the ship, the Spanish Captain Coig surrendered the vessel to Cochrane.

Now came the real moment of crisis. The Spanish shore batteries, numbering over three hundred guns, opened fire on the 'Esmeralda' to prevent her being captured, and it would only be a matter of minutes before they smashed her to match-wood. At such times, those men who are truly great distinguish themselves from those who are merely just brave or foolhardy.

It was dark, and Cochrane knew that the Spaniards would not want to provoke hostilities with the British or American warships in the port. In a move of pure genius, he ordered the lights on the 'Esmeralda' to be set in exactly the same fashion as HMS Hyperion and the USS Macedonian, also both frigates. He knew that there would be some sort of signal to identify friendly and neutral ships should a night attack occur, and simply copied it. The Spanish shore batteries, afraid of hitting these other two ships Ceased fire, and Cochrane was left to sail out his prize unmolested.

Cochrane and the Chilean Navy were now the undisputed rulers of the sea, and took full advantage of this freedom, capturing and looting many Spanish treasure ships. He kept back 285000 dollars of the money he had taken, as payment for his men, who had received nothing in over a year. Notably, he took not one penny for himself.

A Hero's Welcome

Once again Cochrane returned home to a hero's welcome, Faced with that was by nor a total Chilean Naval blockade the last remaining Spanish stronghold, at Lima, had surrendered, and Chile had at last Won its independence. But as before, his victory ass soured. News came from the island of St. Helena that the Emperor Napoleon had died, so ending Cochrane's great dream.

Having won their independence, the Chileans now lapsed into counter revolutions and internal power struggles, and the navy became more and more neglected. He rapidly lost enthusiasm for his Chilean service, and after more disagreements over prize money he eventually resigned his commission on the 18th of January 1823, but not before leaving this final message to the people of Chile:

With these last words Cochrane departed Chile to command the Navies of Brazil and later Greece, helping both countries win their independence and furthering his reputation as a brilliant commander and a liberator.

Returning Home

Cochrane was at last to return home at the age of fifty four and began the long fight to clear his name. On request, he was permitted to submit a review of the Stock Exchange fraud case against him and did so promptly. But there were still a few of his old enemies left in the commons, and so at length, his devoted wife Kitty obtained an audience with the newly crowned King William IV, who subsequently granted Cochrane a Royal pardon in 1832. He was reinstated in the Royal Navy at the rank of Rear Admiral of the Red, and was promoted to Vice Admiral in 1841.

He continued to fight for the return of all his honours, and in 1846 petitioned Queen Victoria to be readmitted to the Order of the Knights of the Bath. Victoria and Albert, both great admirers of the now ageing hero, responded as well as could ever have been expected, restoring him to the order and proclaiming that his knighthood should stand from its original date of 1809. Since Cochrane had never been guilty of any conduct to merit its revocation - he was fully vindicated. In 1855 he offered himself for active service in the Crimean war, but at 80 was considered too old. He died in 1860, and by order of Queen Victoria her hero was buried with full military honours in Westminster Abbey, where a service is still held every year in his honour. He was the last hero of the great Napoleonic age of sail, Lord Thomas Cochrane, Il Diablo, the last Viking, the Sea Wolf.

With special thanks for help in the research and completion of this article to Rear Admiral Jorge Arancibia of the Chilean Naval Commission in London. I am very much indebted to him for his extraordinary generosity.

Related Article

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. As an outspoken critic of naval corruption, and as a radical MP, a constant thorn in the aide of the Government, he had, over the years made many powerful and influential enemies. It is sad, if not somewhat unsurprising, that these enemies would contrive to engineer the fall from grace of the hero of the 'El Gamo', Fort Trinidad, and countless other actions. What could never have been expected, however, is that he would rise again, to become a legend in his own lifetime, outlive them all and ultimately right every injustice done to him.

As an outspoken critic of naval corruption, and as a radical MP, a constant thorn in the aide of the Government, he had, over the years made many powerful and influential enemies. It is sad, if not somewhat unsurprising, that these enemies would contrive to engineer the fall from grace of the hero of the 'El Gamo', Fort Trinidad, and countless other actions. What could never have been expected, however, is that he would rise again, to become a legend in his own lifetime, outlive them all and ultimately right every injustice done to him.

Chilenos - My fellow countrymen!

You know that independence is purchased at the point of a bayonet. Know also that liberty is founded an good faith and on the laws of honour, and that those who infringe upon these, are your only enemies, amongst whom you will never find.

COCHRANE.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #32

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com